Chapter VIII

Closing Days of the New Guinea Campaign

FROM Hollandia the American advance along the Dutch New Guinea coast toward the Philippine Islands moved slowly at first. Although, only slight enemy resistance was encountered, the thick jungle and inclement weather greatly hampered its speed. Why not try another run up the coast? A landing about one hundred miles or so up the coast could probably be made without great difficulty and cut off some of the Japs. Our supply lines would not be extended too far. The enemy still might be off balance as a result of the surprise assault on Hollandia and be toppled over easily. We had plenty of landing craft, naval support and troops readily available. Why not try it?

The village of Sarmi, about 150 miles up the coast from Hollandia, was at first considered as a possible point of attack since it was reported that the enemy had concentrated as many as five thousand troops in that area and that it was only a short distance beyond the Sawar and Maffin airdromes, neither of which were very active but nevertheless, in good operating condition. There was also the possibility that many of the japs had fled from the Hollandia area and had joined these forces at Sarmi. All things considered, it was a likely target. However, it was thought best to postpone the landing at Sarmi until we first held control of Wakde Island and had a fighter strip in operation there. This island, located only a few miles offshore and 115 miles west of Hollandia, possessed an airfield of sufficient size to permit the take-off of fighters and medium bombers. Moreover, its garrison of about five hundred japs was reported to be in the process of evacuation. This information was later proved to be incorrect for by actual count of the dead alone on D+2 there were 759 japs on the island when the landing was made. Certainly our control of Wakde Island would have a decided influence on our further advance up the coast toward Sarmi.

It was finally decided that on the morning of 17 May the initial landing would be made on the mainland a mile or so beyond the native village of Toem which is located directly opposite Wakde Island. That afternoon a subsidiary landing could be made on Isomanai Island between Toem and Wakde Island. The actual landing on Wakde would not be made until the following afternoon. The soundness of the Task Force Commander's request that the landing on Wakde be made on the following day rather than on D-Day as had been proposed was well brought out when the landing was made. Had the landing occurred on D-Day the casualties would have been many times greater and the landing may even have been initially repulsed. One reason for the prior landing on the mainland was to provide a base from which mopping up operations toward Sarmi could later be conducted. But more important than that, it was considered that, due to the probable strong defenses on Wakde, it would be advisable to subject that island to a day of naval and air bombardment before effecting the landing and, since the beach selected was only a little over two miles from Wakde island and well within artillery range, this bombardment could be strengthened by a barrage of 105-mm shells. Tor River, west of the beach, protected it against enemy interference from the Sarmi area. And so the operation was planned.

Sarmi (Toem-Wadke Area) Dutch New Guinea. May 1944. An LCM of

Co B, 542 EBSR is pressed into service as a ferry boat on a jungle

stream.

General Heavey assigned the task of landing elements of the 163d Infantry of the 41st Division at Toem and later on Wakde Island to Company A, 542d EBSR, under the command of Captain (later Major) Ralph W. Jones, Jr. of Townsend, Virginia. On the night of D-1 the convoy of 542d EBSR landing craft and a few naval support vessels left Hollandia under its own power on a direct course to the objective beachhead at Toem. The trip was uneventful, seas were calm, and the convoy arrived at its destination well before dawn. The landing at Toem was unopposed and proceeded according to plan, although, our boats encountered relatively high surf and had to go in on the shallow beach end-to-end. No boats were lost. During the afternoon of the same day, a landing was made on Isomanai Island where slight opposition was encountered. Lieutenant William Stiles, Hq. Co. Bt. Bn., of Shreveport, Louisiana, and Lieutenant William H. Fowlkes, Jr., Company A, of Richmond, Virginia, with a party of two boats, made a reconnaissance of Tor River on the mainland to find a hideout for our craft. During the reconnaissance they were ambushed by jap snipers. Unfortunately, Lieutenant Stiles was killed instantly and Lieutenant Fowlkes was wounded. As soon as possible the patrol withdrew from the area and returned to their base at Toem.

The next afternoon the landing was made on Wakde Island. The Air Force and Navy had plastered the mile-long island from one end to the other for twelve consecutive days. Little if any resistance was expected since the two previous landings at Toem and on Isomanai had been unopposed. However, as a safety measure, the LCM flak boats were present and a rocket barrage was laid on the beach just ahead of the boat waves. Despite the intensity of the bombardment throughout the day before and the naval shelling immediately prior to the actual assault ' the japs managed to get to many of their light weapons in time to open heavy fire on the barges as they plunged toward the shore. It was later discovered that, in addition to these guns, the crafty japs had also taken turrets from disabled planes and dug them into the sandy beach so that only gun muzzles protruded. The first two boat waves were scarcely three hundred yards from the beach when they ran into this hail of machine gun fire from both flanks. The passengers immediately fell flat on the bottom of the boats where the armor plate on the passenger's section of the LCVPs protected them. The boat crews did not have this protection. The coxswains had to stay in an exposed position in order to keep their boats in formation and under control. The bow lookouts had to watch for submerged coral heads and signal the coxswains how to avoid them. In running this gauntlet of fire many of our men were hit, but as soon as a coxswain went down, the engineman or the seaman of his crew jumped up to take over the controls. Not a boat faltered as they plunged into the ever-increasing barrage. All the boats made the beach, although several of them were riddled with bullet holes. After the landing sixty-eight slugs and fragments of a 20-mm shell were found in one barge. Every passenger was delivered safely. The Amphibs chalked up another successful landing, but at the greatest cost of any yet encountered, considering its size. Three men from Company A, were killed: Tec/5 Byron B. Bull of Oak Hill, Kansas; PFC Obie Casey of Dyer, Arkansas and Pvt. Emray F. Clark of Reobens, Idaho. First Lieutenant Donald F. Ridgeway of New York City and twenty-seven enlisted men were wounded.

Wadke Island, Dutch New Guinea. 18 May 1944. Co A, 542 EBSR,

beach boats under heavy enemy fire.

During the run to the beach the coxswain on one of the barges was killed instantly. No other Amphib being close to the wheel which spun madly back and forth, one of the passengers, Richard M. Day, an American Red Cross War Photographer of Kirkwood, Missouri, jumped to the controls and directed the boat until the engineman could take over from him. Mr. Day then helped to operate the ramp winch while the boat was beaching and retracting. In all of this time Mr. Day was directly exposed to enemy fire. This was his first experience in a landing of this sort and his courage won for him the respect of every Amphib and infantryman in the area. A short time later, on the recommendation of General Heavey, Mr. Day was awarded the Silver Star Medal.

Toem, Dutch New Guinea. 17 May 1944. Co A, 542 EBSR LCVPs put

infantry ashore on D-Day in spite of surf and shallow beach.

For their magnificent work that afternoon "in carrying out their mission with unflinching determination and bravery" the 21 officers and 338 men of Company A, 542d EBSR, were awarded the Presidential Unit Citation.

On the same day as the Wakde landing General Heavey received orders to alert one of his regiments and the Brigade Support Battery to participate with the 41st Division in a major landing on Biak Island. This mission was to be run in lieu of any further advance up the mainland toward Sarmi and was actually to be a continuation of the Wakde operation. Since Company A, 542d EBSR, had already been hotly engaged at Wakde and was now busily engaged in lighterage work there, General Heavey picked the balance of that regiment for the Biak mission in support of the 41st Division. The Regimental Commander, Colonel B. C. Fowlkes of Santa Barbara, California, commanded the 2d ESB Task Group, They had just completed their assault on Tanahmerah Bay and had expressed their disappointment at the lack of opposition there. Perhaps Biak would have something better on which they could expend their pent-up energy. It did.

One news reporter claimed that when the future historians record the battle for Biak they will rename it "the buffalo victory." Someday that may be done, for the buffaloes of the 2d ESB Support Battery played a great part in the seizure of that island, but they were not alone. The shore engineers of the 542d were equally as instrumental in that victory and have long record of heroic action to support any claim made in their behalf.

What sort of a place is Biak anyhow? What was to be gained by its capture? Biak Island, located at the entrance to Geelvink Bay and about two hundred miles west of Wakde. is fundamentally one big lump of coral, or, as one writer in Yank Magazine puts it, one hundred square miles of the most useless land ever tossed up out of the sea and one of the better haunts of malaria, dysentery, yaws, tropical ulcers, mosquitoes, flies and crocodiles." The area in which most of the fighting was done was a series of terraced, heavily wooded ridges honeycombed with thousands of caves. Between the two ridges there was a level plain covered with scrub growth. On the plain were three saucer-like depressions connected underground by a series of gigantic tunnels and caverns. Around the inside of each of these depressions were hundreds of small caves. These caves provided protection for the japs throughout our aerial and naval bombardments and were the source of much trouble to our advancing infantry.

How strong a force of japs was garrisoning Biak was the subject of much conjecture. Some reports indicated as few as two or three thousand but the three excellent airfields there led many to believe the japs would have a much stronger garrison. Actually over 8000 Japs were killed in the Biak campaign. Even then many escaped at night to Dutch New Guinea. Biak was never a popular tourist haven. In peacetime only one European lived there. When the Japs arrived they immediately built three airstrips-Mokmer, Borokoe and Sorido and began the construction of defensive positions to protect and operate them. Several naval guns were brought in and installed. A coral reef of “niggerheads” and potholes rings the island making it almost impossible to beach landing craft except in a few scattered locations. That is why the buffaloes were used so extensively.

The seizure of the Biak airstrips would give us a base for our heavy bombers. It had been found that they could not operate efficiently from Hollandia airfields and a reconnaissance had failed to reveal sites suitable for heavy bomber strips west of Hollandia short of Biak. Thus, the Liberators were forced to continue operations from the strips around Finschhafen and Lae pending further operations westward. The strategic urgency of the situation was quite apparent. Moreover, Biak was located well within the enemy's secondary defenses and its capture would give us a base for operations throughout the Netherlands East Indies and, more important, the Philippine Islands.

The 2d ESB craft listed to take part in the initial assault on Biak were 25 LCVPS, 67 LCMS, 1 LCS, and I cruiser from the 542d EBSR and 2 Flak LCMS, 4 Rocket LCVPS, I rocket buffalo, 4 combat buffaloes, 28 troop-carrying buffaloes and 3 rocket DUKWs from the Support Battery. Many more craft were brought in on later echelons. Remember Nassau Bay? Times had certainly changed.

The landing was scheduled for shortly after dawn on 27 May, just ten days after the assault on Wakde. It didn't give us much time, but, just as the number of craft employed in an operation had increased with each operation, so had the tempo. No longer were months or even weeks available in which to plan an operation. Now it was a matter of a few days at most and, in the case of smaller landings, often only a few hours. We had participated in so many landings by the time the Biak show rolled around that we almost knew what to expect and also what to do when the unexpected happened. Nearly every man had been in at least one amphibious landing. For some the number ran into two digits. We were fast becoming veterans.

When the convoy arrived off the Village of Bosnek on Biak Island, the beach was in a mist which was soon thickened by the smoke of the naval bombardment and the bombs dropped by more than fifty Liberators. There was not a drop of wind and the humidity held the smoke down on the beach. All landmarks were blotted out. As a result, the first wave of buffaloes hit west of the proper beach. The error was discovered before the second wave landed, the smoke having lifted somewhat, and it managed to shift west to the proper beach. All subsequent waves landed correctly. Fortunately, the troops landed by the first wave managed to move west by land to join their unit so no damage was done and actually valuable information was gained by them as to enemy disposition. As expected, the fringing coral reefs prevented LCVPs and LCMs from reaching the beach, so they went in as far as possible and the troops waded over the reef to the shore. The large landing craft, LCTs and LSTS, could not get in close enough to unload except at one break in the reef spotted by our reconnaissance party. Here the bulldozers made it ashore under their own power, the drivers being almost shoulder deep in the water, only the frame of the bulldozer and the elevated exhaust pipe appearing above the water. Our men knew how to waterproof their dozers and trucks. Luckily, the two coral jetties the Japs had constructed were found to need only minor repairs by our bulldozers before LCTs and LSTs could disgorge their vehicles on them. In addition to this, our shore engineers installed two pontoon causeways over the reef to deep water. Only one LCT and at a time was able to unload there. so a shuttle was run by them from LSTs out in the stream which could not be accommodated at either of the two jetties. Buffaloes and DUKWs were also kept busy unloading the LS'I's in the stream.

The installation of pontoon causeways at Biak was the first instance of their use in the Southwest Pacific. A shore battalion detail under Major (later Lt. Col.) E. L. Edwards of Columbia, Missouri, did a very efficient job in this, their first job of launching pontoon causeways from an LST and installing them as a dock to shore. They proved very valuable and were slated to be used in many of our subsequent operations. They are difficult to hold in place in a storm or where there are strong lateral currents. Guy lines can be used temporarily but they later have to be replaced by pile clusters.

Except for a few Japs who had taken shelter in caves at the foot of the cliffs behind the beach and from which they continued to snipe at the shore party during the initial unloading phase, there was little enemy ground opposition. The aim of the snipers was fortunately, quite inaccurate and we received no casualties from them. Shortly after the buffaloes got ashore they silenced these snipers with a few rounds of rocket fire. Enemy air opposition was also absent and this was doubtless due to our strong fighter cover that was present throughout the attack. However, just before nightfall five Jap planes did attempt to strafe the beach. Our fighter cover had left for the day. One Betty dived for the LST on which General Heavey and his Aide, Captain Barron Collier Jr., of New York City, were conferring with some naval officers. Three bombs and a hail of fire were on the way from that Bettv before the plane was even seen. Caption Collier was hit by seven fragments from a 20-mm and one of the bombs hit the deck ten feet from where the General and Captain Collier were crouching. Luckily, the bomb was a defective one for it split in two, sprinkling the deck with picric acid, but there was no explosion. Another bomb hit an LCVP alongside the LST and destroyed it. The other four Jap planes went for the naval ships after strafing the beach. One crashed into the stern of a PC and inflicted a number of casualties. Another blew up only a hundred feet from an LST it was attempting to crash. A third one missed the bridge of a destroyer by only ten feet and exploded as it hit the sea. Not a plane got away, This air attack was only an indication of the violent air reaction to come from the japs in the next fifteen days. He was upset over our advance closer and closer to the Philippines.

The entire beach on D-DAN, showed evidence of the terrific bombing and shelling during our assault. One Jap six-inch naval gun in a turreted emplacement had suffered a direct hit from a large bomb. A five-inch naval gun in a turreted emplacement had been destroyed by the naval gun fire or the rocket fire from our rocket LCMs. Another five-inch naval gun that had also been placed in position was rendered useless by our strafing planes. Several wrecked searchlights were found.

Although there was not much energetic ground opposition during the initial landing, there was plenty of it waiting in the hill caves. Perhaps the Japs had planned to wait until darkness and then infiltrate through our lines to annihilate the invaders of their peaceful domain. If so their plan was nipped in the bud. The initiative and aggressive action of three officers and five enlisted men of Company E, 542d EBSR, and two enlisted men of the Support Battery resulted in the elimination of two Japanese strongholds in the cliff commanding the new beachhead and in the death of almost one hundred Japanese officers and men.

Shortly after noon on D-Day Captain (later Major) Don D. DeFord, the Commanding Officer of Company E, of Elwood, Nebraska, was on a reconnaissance along the bottom of the cliff to locate a route for an interior dump road from the beach's right flank. Behind him 1st Lieutenant Byron Brim of Hudson, Kansas and 1st Lt. (later Captain) Grady F. Rials of Jayness, Mississippi, were operating a bulldozer to open the route pointed out by Captain DeFord. When they came opposite two caves overlooking the center of the beachhead they were stopped, by an infantry patrol who said that their officer had just been killed by Jap snipers shooting from the caves. They added that they couldn't approach the officer or the caves to throw hand grenades because of rifle fire from the openings. They asked for assistance. Captain DeFord immediately sent back to his company for two rifle grenade dischargers, more hand grenades and additional men. In a few minutes up came the grenades and Cpl. Charles Smith of Jasper, Alabama; Pvt. Joseph W. Lorek of Cleveland, Ohio; Cpl. John P. Martin of Los Angeles, California; Pfc. Stanley R. Archacki of Cleveland, Ohio, all of Company E, 542d EBSR; and S/Sgt. Paul E. Broomhall of Sclotoville, Ohio; and Private William L. White of Kansas City, Kansas, both of the Brigade Support Battery.

The rifle grenades were fired into the two caves and at the smaller openings that were used for sniping. The main entrances of the two caves were about fifty yards apart. Lt. Rials then took a group of men to see if a rescue of the infantry Lieutenant could be effected. More rifle grenades were fired into the mouths of the caves. When the situation permitted, they went forward and found that the infantry officer had been shot between the eyes. Meanwhile, Captain DeFord and Pvt. Lorek had taken another route through the underbrush until they were only about ten feet from the left cave. Hand grenades were hurled and the enemy was silenced. Leaving four men to guard that opening, attention was directed on the right cave. Captain DeFord was charged by a Jap officer and an enlisted man who came from the mouth of the cave with bayonet gleaming and evidently intended to be used. Within five feet of Captain DeFord the Jap officer was shot down by the Captain, Lieutenant Rials ind Lt. Brim, all of whom put 45-caliber slugs into his head and chest. Lts, Brim and Rials and Cpl. Smith killed the enlisted man who was charging Captain DeFord with the bayonet. During this action Pvt. Lorek was wounded. Returning to the cave they could hear japs talking inside. Captain DeFord demanded that they surrender and, when no response came, additional hand grenades were hurled into the cave. Lt. Brim, Cpl, Smith and an identified infantryman, the only member of the original patrol who took part in the action, ventured into the cave's entrance where they received a burst of rifle fire. The infantryman fell but was pulled to safety by the other two men. He was not seriously wounded.

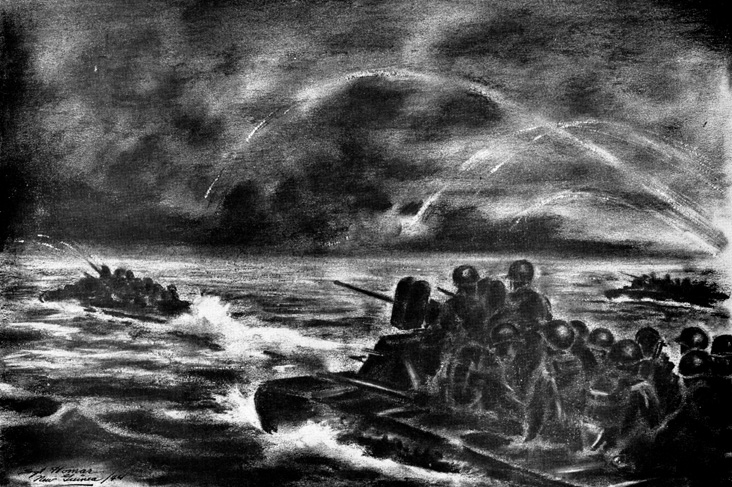

Buffaloes going in at Biak. LCI covers them with rocket barrage. One buffalo (upper left) fires several rockets.

2nd Amphibious Brigade Support Battery. Drawing by Sgt LN Homar.

S/Sgt. Broomhall and Pvt. White from the Support Battery now arrived with a bazooka and a tommy gun. They fired about six rockets from the bazooka into the cave and this time when the patrol entered they encountered no fire. They found about sixty dead japs in one of the "rooms." This operation was repeated in the first cave and all further opposition was eliminated. A guard was placed around the caves and the rest of the party returned to camp. The next day Captain DeFord found several chests of company records in the caves. About one hundred Japs were also found - all dead. One had destroyed himself by discharging a U. S. carbine rifle in his mouth. A couple of days later they went back to count the actual number killed and to bury them. The counters were driven out by the stench and thoughts of bringing them into the open to bury them were abandoned. The mouths of the caves were sealed by blasting. For his courage and heroic action in wiping out these enemy strongholds, Captain DeFord was later awarded the Silver Star Medal. Further up the beach that same day Lt. Jonathan J. Norris of La Union, New Mexico was leading a small patrol of shore engineers from Company D when grenades were tossed at them from another cave. They moved in close to the cave and pitched their own grenades into the entrance. When the smoke cleared, they entered and found two japs riddled by grenade fragments. Fortunately the Jap grenades did not wound any of our men.

In addition to performing lighterage duties between the ships in mid-stream and the supply dumps on the beach, the buffaloes of the Support Battery were used to carry ammunition and supplies to the infantry advancing along the coastline in each direction from the beachhead. On most of the "end run missions" they were subjected to heavy enemy fire from shore batteries. Occasionally, Jap planes would sneak in low over the beach in a lightning strafing attack. It was during one of these raids that the men on the buffaloes of the Brigade Support Battery definitely shot down six planes and two others that they listed only as probables. A couple of days after the assault a convoy of about eighteen buffaloes loaded with supplies and ammunition went by water up the coast to the vicinity of Parai jetty not far away from the original beachhead. When they arrived they found the infantry battalion in a very bad position surrounded on all sides except the sea. Their commander ordered an immediate evacuation by water. This movement was carried out under fire with the combat buffaloes and flak boats rendering noble service in the destruction of several enemy mortar and sniper positions. Every man, including all the wounded, was safely evacuated to the waiting landing craft that took them back to Bosnek.

Biak Island, Dutch New Guinea. 27 May 1944. “Alligators” LVTs)

of 2 ESB Support Battery rest on beach after putting infantry

ashore. Rocket alligarot in foreground. LST jetty in background

constructed by 542 EBSR Shore Bn.

Noemfoor, Dutch New Guinea. 2 July 1944. After routing the Japs

from the air-strip the 2 ESB Support Battery Buffaloes fly some

souvenirs.

Flak LCM No 320. Close-up of the Martin turret

twin 50 cal. machine guns with gunners in

position. 75 mm Air COrps cannon can be seen

in the bow.

Noemfoor, Dutch New Guinea 2 July 1944.

Coral reef exposed at low tide over which

“Alligators” of 2 ESB Support Battery carried

first assault troops.

One evening a report was received that an enemy fleet was headed from the Philippines toward Biak. Plans were made for an evacuation from the beaches into the hills. It would have been a forced squeeze play with the Yanks in the middle, but fortunately, the Jap fleet did not appear. An American naval force and planes from Wakde had intercepted it near Halmahera and sent it scurrying it other directions.

A few days later the Support Battery buffaloes were again used to assist an infantry battalion trapped in the vicinity of Mokmer airdrome just a short distance beyond Parat jetty. 1st Lt. Donald B. Davis of the Support Battery with a flak LCM and ten buffaloes waited off the Mokmer beach with supplies of food, ammunition and AA equipment. 1st Lt. (later Capt.) Edwin T. Stevenson stood by with four rocket LCVPS. As soon as the unloading commenced the enemy opened with a terrific mortar and machine gun barrage. The flak LCM returned the fire and stayed on the beach until the Supply-laden buffaloes could safely retract. Shortly after midnight a new landing was attempted and this time a rocket barrage was laid on the enemy gun positions by the four rocket barges. A battalion of infantry was taken ashore despite sporadic rifle fire from both flanks. After the troops were safely ashore, ninety-two casualties were taken aboard the buffaloes and ferried to landing barges that were waiting offshore. The coral along the beach had prevented the LCVPs and LCMs from landing so this shuttle service was the only means of getting men in and out. In this action an enemy plane dropped a bomb among the buffaloes on the beach and seriously damaged several of them. Four men were wounded. One man, Tec. 5 Hiram P. Lankford of Ashville, North Carolina, was killed by sniper fire. During the night the remainder of the supplies were ferried ashore and the infantry battalion's serious predicament was greatly alleviated. On the return trip from Mokmer airdrome the next morning the rocket barges laid another barrage on the cliffs behind Parai jetty. This reduced the enemy strength to such an extent that later in the morning the infantry forces were joined in that area and the entire beach from Bosnek to Mokmer was in our hands. The Support Battery continued their shuttling of supplies for a few more days until they were relieved and sent back to Wakde to prepare for a new operation. They had done a grand job.

For their outstanding performance of duty in action against the enemy on Biak Island from 27 May to 14 June, the date they were relieved, the Support Battery was recommended for the Presidential Unit Citation. The rigor of their service in the face of intense enemy fire is demonstrated by the fact that only seven buffaloes remained operative out of the original fifty-four with which they started the operation. Through their tireless and gallant efforts the capture of Mokmer airdrome was made possible. The lives of many casualties were saved due to their prompt action in evacuating them from the forward beachheads. Their citation ends with the following sentence:

"Acts of gallantry and heroism were numerous but difficult to single out of the uniformly high standard of achievement set by all personnel of this unit."

During these operations our craft was subjected to frequent air attack and succeeded in shooting down several planes. One day a lone LCM was pushing along the northern coast of Biak to take supplies to an outlying infantry patrol. On the way one of the crew saw a few hundred yards off shore an unusual island massed with underbrush and low coconut trees. To be on the safe side against an enemy sniper, he gave it a burst of machine gunfire and was surprised to receive machine gun fire in return. Maneuvering to bring both their .50-caliber machine guns to bear on it, the gunners raked the small island for several minutes. All fire from the enemy having ceased, the LCM cautiously closed in and to their surprise found the "island" was a jap landing craft heavily camouflaged. It contained several dead Japs and some important documents which were turned in to Army Intelligence.

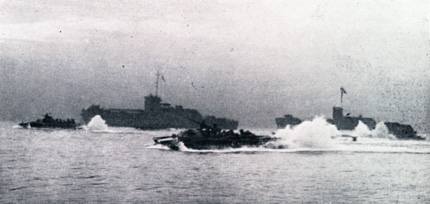

Noemfoor, Dutch New Guinea. 2 July 1944. Buffalo troop carriers of

Support Battery, 2 ESB, launched from LSTs, carry first troops ashore.

Landings were subsequently made by the 542d boatmen on Owi, Woendi, Pai and Aeoki Islands. No serious opposition was encountered. Air raids continued as an almost nightly occurrence and a few more casualties were sustained. As the Yanks moved on to take one after the other of the islands of the Schouten group, the size and intensity of these attacks gradually lessened. Soon life returned to "normal" for the men of the 542d. They had worked hard to secure Biak Island and they had ample cause to refer to it as "their home." They stayed there until late fall and still boast about all the "comforts of home" that they installed for themselves. They had clubs for both the officers and enlisted men, recreational areas, fine movie area, baseball diamonds, and other conveniences. Everything suited them perfectly and their days on Biak will always be one of their more pleasant memories of whatever pleasure they could garner in the isolated islands of the Southwest Pacific. All agreed Biak was better than Port Moresby or Milne Bay, especially on weather and mosquitoes.

The 2d ESB concluded its operations in the New Guinea campaign by participating with the 3d ESB in the assault on Noemfoor Island on 2 July 1944. This was our thirty-first amphibious landing. The coral reef that fringed Noemfoor was even worse that at Biak so landing barges were not even used in the initial assault. The buffaloes were the only vehicles that could clamber over the coral with comparative ease, so the Brigade Support Battery was the only brigade unit in this operation. At high tide the treacherous coral lurked just below the surface of the water and at low tide it was only a few inches above the water level. A DUKW outfit that went along to assist in lighterage work found the sharp coral with its deep potholes rough going and the loss in DUKWs hardly made their employment worth while. Our buffaloes were kept busy towing the DUKWs over the jagged coral.

Preparation and staging for the operation in Support of the 6th Division, a new unit to us, was held on Wakde Island. The entire task force was known as the Cyclone Task Force. The Amphibian mechanics worked steadily for several days and nights just prior to the convoy's departure repairing the damage caused to the buffaloes by shrapnel and the coral reef at Biak. About noon on 30 June the convoy with the buffaloes loaded in LSTs left Wakde. The next day they passed Biak, and at dawn the following morning they were in position off Noemfoor Island. Fortunately the sea was calm enough to lower the great ramps of the LSTs and launch the amphibious Buffaloes while at sea.

The combat buffaloes hit the beach first. Close behind them three waves of troopcarrying buffaloes crawled across the coral. The site selected for the attack was in the vicinity of Kamiri airdrome on the northwest shore of the island and fortunately no opposition was encountered where we landed. The Japs had made ample preparations for our attack. If our troops had attempted to land about a thousand yards west of the spot actually chosen, they would have had a rough go of it. As it turned out, the Japs were unknowingly flanked. The combat buffaloes immediately fanned out when they hit the airstrip. Several Japs had set up gun positions on the seaward side of the strips to prevent an amphibious landing and, when they saw our buffaloes (tanks to them) on the airstrip to their rear, they made a dash for the caves on the other side of the strip. They were like targets on a shooting gallery. The buffaloes immediately opened fire and thirty-nine japs fell dead. Some, however, did make it to the caves and pillboxes on the opposite side of the strip and from those positions returned the Yank fire. The buffaloes used their 37-mm guns and rockets to knock out one pillbox after the other. Over eight hundred rockets were fired that day. The Support Battery's final score for D-Day was sixty-seven japs definitely killed in direct action and an unknown number undoubtedly killed by rocket fire, strafing and flame-throwing attacks on pill boxes and caves. General Patrick (later killed in the Philippines) the Cyclone Task Force Commander, stated in his report after the Noemfoor action:

"The Support Battery unhesitatingly used their light amphibious vehicles as land tanks advancing to within several feet of the fortified entrances and blasting the positions with flame throwers and automatic weapons. The use of amphibious vehicles as tanks against fortified positions armed with mountain guns and 37-mm cannon, a use beyond the capabilities for which the vehicles were designed, was an exhibition of gallantry which I consider deserving of special commendation."

There is one incident during this action that will always get a laugh from those who were present. Major Charles K. Lane, the Support Battery Commander, was in the lead buffalo during the attack on the airstrip. When the firing had stopped for a minute or so, he gave instructions for his men to stay on their vehicles and under no condition to dismount. Then he fearlessly got off and went from one Jap body to the other "looking for documents”. He found a nice Jap officer's saber, Jap flags, watches and other valuable souvenir items. Just then the Japs fired a burst of machine gun fire in his direction and he hit the dirt. Rockets from the Buffaloes silenced the enemy gun and Major Lane crawled back aboard his Buffalo unhurt. They kidded him with "You stay here and keep me covered, boys. while I get the souvenirs." Of course, that wasn't his intention at all - or was it? Nevertheless, for a minute all thought of their immediate danger was forgotten by the men. A laugh does things like that. You relax for a while and then you're ready to start all over again.

The troop-carrying Buffaloes ferried men and supplies ashore throughout the day. They towed disabled DUKWS, artillery pieces and vehicles of all types across the coral and over the sand beach to the airstrip. As has already been stated, these Buffaloes were the only vehicles, except the DUKWS, that could navigate the rough coral and, without their support it is doubtful if a great amount of the necessary equipment and supplies could have been landed promptly.

After the airstrip was in our hands the infantrymen and Amphibs who were scattered throughout the area were surprised to see the sky suddenly filled with paratroopers rapidly descending to earth. It just so happened that when they arrived the action was mostly over, but there is also the possibility that, had we landed in front of the Jap beach guns. as we nearly did, these paratroopers probably would have saved our necks.

A couple of days later the Buffaloes were used again to carry an infantry task force around the end of the island and land them in the vicinity of Nember air-strip on the southwestern shore of the island. No opposition was met. Evidently the Japs had displayed their strength on D-Day for within a week the entire island was in our hands. Most of the remaining japs were disorganized stragglers in the mountains. Our advance was resisted by a few stray snipers here and there but they were quickly eradicated with little damage. The Support Battery reloaded in LSTs and returned to Wakde about the middle of July.

Insofar as actual combat with the enemy is concerned, the Noemfoor operation closed the New Guinea campaign for the 2d ESB. Plans were already underway for our participation in the Philippine Campaign. Perhaps it is a good idea to pause for a minute and review the location of the brigade units at, let us say, the time of the Noemfoor operation or the first part of July, 1944. Which units were where and what happened next?

The Brigade Headquarters, 162d Ordnance Maintenance Company, 287th Signal Company, Quartermaster Headquarters and Headquarters Company and the Brigade Medical Detachment had moved from Oro Bay to Finschhafen early in April. They erected an excellent camp on a small point just opposite Launch jetty. It will be recalled that the 532d boatmen had used this jetty in their resupply mission to the Aussies during their drive on Finschhafen a few months before. These units stayed at Finschhafen until they moved to Hollandia early in October. During this period the brigade received over a thousand new replacements and were rapidly assigned to vacancies in the various brigade units and trained in their new jobs. Transportation was a difficult problem and these men often had to wait two or three weeks before they reached their assigned unit. In the meantime a course in amphibious tactics, boat operation and jungle fighting was conducted for the men. In the evenings the troops of the service units attended classes in Shorthand, Typing, English, Physics, Accounting and Music which were conducted by brigade officers as a part of the Army Educational Program. About this time the brigade received furlough quotas for men to go to Australia "for rest and recuperation." Under these quotas approximately 35% of the brigade got a chance to see the sights of Sydney. Since most of these leave ships embarked and debarked at Finschhafen, the furloughees waited at the brigade transient camp where accommodations were better than at the base staging area. The story of "What happened in Sydney?" is left to the discretion of the individual story-tellers. Good enough? The tales of Sydney are "sumthin."

The behavior of the members of 2 ESB in New Guinea and while on leave in Australia had been exemplary. A few men "missed" their boat returning from Australia after their leaves expired, a few were arrested for taking on too much "liquid cheer". But not a single serious case, such as rape or the like, marred our record. The boys with the blue and gold amphibian shoulder patch were a well behaved group.

The 542d was well established at Biak and the 532d was at Hollandia where they were busily engaged supporting Base B. The 592d was split between Sarmi and the Admirality Islands. The 562d Boat Maintenance Battalion had a fine set-up at Hollandia with one company (1460th) at Biak and another (1458th) at Wakde. A detachment under 1st Lt. John E. Duffy of Washington, D. C., was well established at Manus in the Admiralties which by this time was developing into a large naval base.

When the Brigade Headquarters finally got transportation to take those separate service. units to Hollandia, they found themselves pushed for time. They had loaded all equipment aboard the Liberty Ship "Samuel K. Barlow" at Finschhafen in anticipation of only a short run to Hollandia where no combat would be involved. When they arrived at Hollandia they were greeted with the news that they would have to completely unload the ship and reload all equipment aboard two LTSs and the same Liberty ship in time for departure of the Leyte convoy on 12 October. There was no time to set up complete installations at Hollandia. Instead the men worked day and night in unloading and releoading the ships. It was a difficult task, but their perseverance completed the job in record time.

The three companies of the 262d Medical Battalion were located with each of the three regiments: Company A with the 592d EBSR had just moved from the Admiralties at Toem; Company B was with the 532d EBSR at Hollandia; and Company C was attached to the 542d EBSR at Biak. The battalion Headquarters had just recently moved to Hollandia.

The units of the 562d Engineer Boat Maintenance Battalion were faced with the tremendous job of checking every brigade boat and putting them in first class shape for the Philippine Operations. The boats were called in, a few at a time, for a complete inspection. Shafts, props, ramps and hulls were carefully inspected and, where necessary, new equipment was installed. The engines were given a complete overhaul job. Hulls were scraped and repainted. Not a boat nor a part of any one boat was overlooked. The splendid job they did during those last two months on New Guinea is shown in the fact that not one boat faltered due to inadequate maintenance during the initial assault in the Philippines when they were critically needed.

All of our boat companies were busy on lighterage work at various bases in New Guinea from Milne Bay to Biak and on resupply missions to infantry units mopping up the by-passed jap installations. Our shore engineers were furnishing hatch crews and dock details at the larger bases where countless ships from the United States were arriving daily. It was obvious that preparations were under way for another major operation. We did not participate in the assaults on Halmahera and Moratai, but when these islands were under American control, we were certain that the coming operation would be "somewhere in the Philippines." Even the Japs were wise to that much but what they did not know was where, or when the blow would land. That was our most closely guarded secret.

The first plan was for a landing on Mindanao which the 3d Brigade would support. In late September, however, we received orders for our participation in the Philippine show. Having been previously informed that we would not go with the first attack force, we had not rushed our planning and preparations to a great degree. However, these orders were entirely different! We found that we were included in the Sixth Army units to land on Leyte, one of the Philippine Islands, in less than a month and from that time we would have to deduct at least a week for the trip itself. This gave us about twenty days to make all final preparations.

It was nip and tuck for our units to disengage themselves from the jobs they were doing and, to get set for the new operation. Most of the 592d regiment had to move its boats and equipment from Wakde to Manus, some 600 miles, to stage with the 1st Cavalry Division. Fortunately, the 532d Regiment at Hollandia was working near the unit with which it was to stage, the 24th Division. The Brigade Special Troops had to move from Finschhafen to Hollandia to stage with the Sixth Army Headquarters. The part of the 542d Regiment that was included in the operation had to move 300 miles in its own craft from Biak to Hollandia while the rest of that regiment had to continue operations at Biak until they could be released to join us in the Philippines. All of these shifts had to be completed by 12 October when the D-Day echelon would complete its loading. Every care had to be taken to have with us every essential item of equipment, for we were jumping eleven hundred miles this time. The move from Finschhafen to Hollandia had given us an idea of what to expect in that line. Nothing could be forgotten - not even a single one of the six thousand different boat parts needed to repair our landing craft. This was not like the Normandy invasion where it was only fifty miles back to a base. There a small boat could go back and get in a day any needed item. Not so on the invasion of the Philippines!

Due to the distance involved and the possibilities of typhoons and to the fact that we were crossing water probably infested with enemy submarines, it was necessary to work out a plan to lift all our small craft and to get at least two fuel barges to the far shore during the early stages of the operation. We planned with the Navy to use their facilities to the maximum to get every possible boat to the Philippines.

The final plans as worked out involved transporting over four hundred craft of all description. This operation was even larger than the Hollandia trip where we used the unprecedented total of 280 landing craft. In addition to these Navy-transported craft, our two small sea-going tugs with four fuel barges and four crash boats were prepared to make the long trip from Hollandia to Leyte under their own power in a slow convoy. Everything went as planned except for one incident which came to be known as "Snell's Odyssey."

1st Lt. George V. Snell, 542d EBSR, of Providence, Rhode Island, was in command of eight LCMs that were loaded aboard a Navy transport at Hollandia for shipment to the far shore. After they were loaded, the Navy skipper of the ship got new orders. To Lt Snell's consternation he found after he was at sea that the ship was headed for New Caledonia, two thousand miles to the rear, rather than to the Philippines. For the next three months he and his boat crews were virtually in the Navy. They did not get to the Philippines until they landed at Lingayen with the 4th ESB the early part of January, 1945. A short time later they rejoined the brigade at Leyte with tales of their wanderings from New Guinea to New Caledonia, Guadalcanal and Bougainville where they rehearsed for the landing on Luzon.

During the eighteen months from May 1943 to October, 1944, that the 2d ESB was in New Guinea we chalked up a record of which we were mighty proud. When we closed our books on that campaign, we had credit entries in our work against the Japs as follows:

- Successful assault landings 31

- Enemy casualties definitely inflicted: 795

- Jap prisoners taken: 126

- Jap planes definitely shot down: 22

- Jap barges captured or sunk: 107

But, as the saying goes, "That was only the beginning, folks, only the be-e-ginning." The big job, the one for which we had been priming ourselves since our days at Camp Edwards,-the invasion of the Philippines-was directly ahead. How would our scoreboard read at the conclusion of that campaign?

|