Chapter I

Early Days on Cape Cod

THE 2d Engineer Special Brigade was born on the sandy shore of Cape Cod, Massachusetts, on 20 June 1942. There was no celebration. There was no publicity, On the other hand, everything was “SECRET”. Announcement of the event was proclaimed only by the roar of motors and the sight of queer looking landing craft splashing through the choppy waters of Nantucket Sound. The new brigade’s first day of life was a day of work.

Although training of the new unit was veiled in secrecy, it was not long before the local residents of that picturesque cape showed keen interest in the “boys with the boats”. Little was known about the military newcomers. There were men, and there were boats. Maybe they were like the British Commandos. Maybe not! But gradually they began to refer to the new Amphibians as “Cape Cod Commandos” The men of the 2d Brigade heard and joked about their new nickname. They seemed to enjoy the implication, but they were always quick to explain to a listener just why the name didnÕt exactly fit. “Commandos hit and run. We hit but we don’t run.”

However, the name stuck. It followed them across the United States and the Pacific Ocean to Australia, New Guinea, New Britain and the Philippines. When tropical typhoons or Jap gunfire made their situation precarious or unpleasant, there was always someone to yell, “Come on, you Cape Cod Commandos”. And they did. When they were lonely and tired, there was always someone to jokingly say, “Snap out of it, you Cape Cod Commandos, and laugh”. And they did.

But what about those first few months of the brigade’s life that were spent on Cape Cod? Why are they always brought into a discussion on the brigade history? Why will they never be forgotten? Those were hectic days. The long hours, hard work, strict discipline and rugged living conditions were such a complete reversal of their previous army or civilian life that you couldn’t blame the men for griping. But what they went through there was worth it. More than once it has paid dividends when the chips were down.

The present 2d Engineer Special Brigade was originally known as the 2d Engineer Amphibian Brigade. For the first six weeks of its existence it was under the direction of the Engineer Amphibian Command and its Commanding Officer, Daniel M. Noce, Colonel, CE.

This period was spent mainly in getting organized, equipped and schooled in basic elements. Why the Engineer Amphibian Command and its separate brigades were formed and how personnel for these brigades was obtained is in itself an interesting story that can well be told here. The declaration of war against the governments of Italy, Germany and Japan was the signal for the best military and naval strategists in the country to bend every effort toward the planning of methods to combat the modern bleitzkreig type of warfare employed by our enemies. One of the major problems confronting the high command was that of getting at the enemy most effectively We could have the tools of war and the men trained to use them, but they would be of no value unless they could be transported into enemy strongholds. The solution of the problem was the development of amphibious warfare. It was not a new idea, nor was it to be used for the first time in history. Inherited from Scipio who crossed the Mediterranean, from William the Conqueror who took an army across the English Channel and from Washington who crossed the Delaware, it remained for the Army and Navy to modernize it to meet the present emergency.

Six months after the attack on Pearl Harbor the War Department formed the Engineer Amphibian Command for the purpose of organizing and training army personnel in the operation of landing craft and the establishment of beachheads. Although security restrictions prohibited widespread publication of this new type of unit, knowledge of its existence and the general nature of its duties created interest among civilian boating groups and military personnel who possessed marine experience either as a hobby or as an occupation. The Army Recruiting and Induction Service ran advertisements in leading newspapers and distributed pamphlets through coastal areas to attract men to the “Water Taxi Service”. While classed as an Engineer Unit, the Amphibian Engineers drew officers and men from all branches of the Army. Officers from the Navy, the Coast Guard, the Marine Corps and the Coast and Geodetic Survey were detailed to act as instructors in their specialties. Seaman from the merchant Marine, masters of vessels on the Great Lakes and amateur yachtsmen from Long Island Sound and Lake St. Clair volunteered. Contractors, road builders, carpenters, warehousemen blacksmiths, longshoremen, mechanics and boat builders joined. The percentage of volunteers to undertake this new type of training exceeded all expectations. Some men selected the Amphibian Engineers because it held promise of early and hard-hitting conflict with the enemy. Their expectations were realized, for, less than a year later, they were “hitting the beach” in enemy-held territory.

As rapidly as possible nearly four hundred officers and over seven thousand men were assigned to duties in the 2d Engineer Special Brigade. The manner of assignment is still the butt of many jokes, but three years later the number of men still doing the job to which they were originally assigned indicates that it wasn’t so badly done.

Skillful boat operation was the goal of the preliminary training. Under the watchful eye of Donald C. Hawkins, Colonel, CE, the men were taught the feel of the boats and the rudiments of navigation. He believed that actual experience is the best teacher, so the men learned boat operation the hard way - with plenty of long, hard work and little sleep. But they never forgot what they learned. The men still say that those days under Colonel Hawkins “separated the men from the boys” among the boatmen. Their first job was to establish a camp at Cotuit cut out of virgin forest. No sooner was the camp completed than an extension of the Amphibian Command required a move to Washburne Island at Waquoit, the first real home of the 592d Engineer Boat Regiment. It was later split to furnish a Boat Battalion to each of the three regiments of the brigade.

At the same time, the shore engineers were getting their initial training under Lieutenant Colonel (later Colonel) Robert J. Kasper of Carmel, California, in Camp Edwards proper. Basic training as engineer soldiers and training in operation of the many types of heavy engineer equipment with which the brigade was to be equipped were prime considerations.

The nucleus of the 562d Engineer Boat Maintenance Battalion was formed at Osterville where a boat yard was taken over by the 562d Engineer Boat Maintenance Company under Captain (later Major) John A. Wells of Louisville, Kentucky. This company had some of the best boat mechanics in the United States. Their ingenuity and originality in keeping craft running when parts were not available later in the Southwest Pacific paid great dividends.

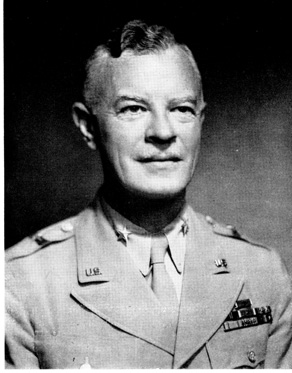

Photo of Brigadier General William F Heavey

During this period the 262d Medical Battalion was activated at Camp Edwards. By the end of July it was fully organized and operating with Major (later Lt. Col.) Fielding M. Pope at Brownwood, Texas, in command. The battalion engaged in landing maneuvers during August with the boat and shore regiments where medical deficiencies and difficulties were discovered and ironed out, and soon “the medics” were becoming a smooth working part of the Amphibian team.

Our “spare parts” companies, all important to the functioning of a brigade, were also being formed at Camp Edwards during this period.

Early in August 1942 William F. Heavey, Colonel, CE, arrived from the Louisiana Maneuvers and took command of the brigade. Graduated from West Point in 1917, he had seen nine months combat service in France in 1918. He admitted that his experience with boats was not extensive but that he was ready to learn all about them and to do everything in his power to make the 2d Engineer Special Brigade a unit that would bring honor and credit to the Army of the United States. As this story unravels, it will be seen how gradually but surely this objective was accomplished.

A large number of carefully selected men were first sent to various schools through- out the country for specialized training in boat operation and maintenance. Some of these schools were the Gray Marine Diesel School in New Orleans, the General Motors Institute in Detroit, and the Chris Craft Hull and Repair School in Algonac, Michigan. These courses were most intensive and covered in detail every step in complete boat maintenance procedure. When the men returned to the brigade, a program was immediately started in which they instructed their fellow Amphibs in the methods they had learned.

As soon as organization and basic training were completed, the program was stepped up. Simulated combat operations were planned and executed. Working at first with small units and later, as more craft became available, with battalions and regiments of the 45th Infantry Division, the brigade landing barges ploughed through the rough waters off Cape Cod to land these infantry troops on Martha’s Vineyard - a beach presumed to be enemy territory. Transporting battle-equipped infantry soldiers, supplies, equipment, field pieces, motor vehicles, dozers and tanks they strove to achieve the split-second accuracy in timing which is of primary importance in amphibious operations. The boatmen first had to learn their boats, how to land them in surf, keep them from being broached and then retract off the beach through the surf to bring in more troops and supplies. It was a job that could be learned only through bitter experience. They had to learn how to move in wave formation of eight to twelve boats with various maneuvers for approach at night or under fire in the daytime and how to deploy when attacked from the air. Then followed training in larger formations finally concluding with an entire boat battalion of 120 craft in one operation.

The shore units, at first divided into “near shore” and “far shore” companies, participated in these practice landings by loading and unloading boats and setting up shore installations on the presumed enemy territory. The original idea was to have a near shore company, trained in the proper methods of loading boats to capacity and still not destroy their equilibrium, remain on the friendly shore and load ships embarking on an operation. The far shore company would establish the beachhead in enemy territory. Its mission included building landing ramps for the amphibious vehicles, clearing the beach of obstacles and mines, constructing exits from the beach proper and many similar jobs. In addition to unloading ships, the far shore companies would protect the newly-won beachhead from enemy counterattack, either by land and sea, or air. They had to make preparations to facilitate the handling of the expanding amounts of supplies and the increased number of men that would arrive in subsequent waves. It was later learned through actual operations that the work on both the near and far shores could best be handled by the same company, so the shore company that loaded a ship was also placed on the enemy shore in time to unload that ship when it arrived. These shore engineers also had to be efficient combat soldiers and trained to fight. More than once the men of the shore companies and the boat companies too have demonstrated their ability to fight as infantrymen to hold and establish their objective beachhead.

Initially the majority of the landing craft used by the brigade were LCP(R) s and LCVs. Some were gasoline operated and some used diesel fuel. The LCP(R) was used for the transportation of personnel and the LCV for vehicles. Throughout this story the type of landing craft used for particular operations will be indicated by initials. To assist the reader, the prefix “LC” means “Landing Craft”. Thus, LCP(R) means “Landing Craft Personnel (Ramp)” and LCV stands for “Landing Craft Vehicle”. At this time the brigade had only a few of the larger craft called the LCM (Landing Craft Mechanized), which was later to become the standard craft of the brigade. Much larger than the LCV and diesel operated, it could weather rougher seas, travel longer distances and carry more cargo and personnel. Occasionally LCTs (Landing Craft Tank), crewed by the Navy, participated in the problems of the brigade. To look back now at those early days and to compare those efforts with the large-scale operations in the Philippines, one is inclined to classify the Brigade’s early maneuvers on Cap Cod as “small time stuff”, but they laid the groundwork upon which the success of later operations was based. Here the decision was made to adopt diesel operated LCMs and LCVPs as the basic craft for the brigade.

One event that is always called to mind when relating the experiences of the brigade on Cape Cod is “that parade”. On September 10th the brigade had been fully formed and at least fairly well equipped. With the band playing and flags unfurled, the boat and shore engineers of the brigade went through a complete parade carrying not only their weapons but also the anchors, tool kits, medical chests, rope or various other odds and ends of equipment to designate the duty they performed. Wearing their heavy rubber parkas and paratroop boots, the men sweltered under the hot September sun. It was a unique and colorful spectacle giving all some idea of the variety and immensity of the unit. Brigadier General Noce, Commanding General of the Engineer Amphibian Command, joined General Heavy in taking this remarkable review. It was later repeated for a large group of senior Army and Navy Officers from Washington.

During the 2d Brigade’s last few weeks on Cape Cod it lost nearly three thousand men through group transfers as cadres for other amphibian units. It seemed as if those long hours of boat and shore training were almost in vain, because no sooner did a man get fairly well trained in his job than, Zingo!! he was gone and a new man arrived to be trained from the bottom up. Despite all this exchange of personnel, the work of the brigade continued without much interruption. The training with the 45th Division ended with a problem which did not go off too well. Some waves of boats got lost at night in the murky waters off Martha’s Vineyard and failed to land on schedule. All made it to the far shore but things did not click. Everyone was convinced the Amphibian’s job was no easy one and, with this in mind, they became more determined than ever to solve all problems, overcome all difficulties, and become an outfit that would always “Put em across” on time and at the right place.

Brigade Officers at final review of 2d Engineer Amphiban Brigade,

Fort Ord, California

While the 2d Brigade was being formed as a part of the Engineer Amphibian Command, another unit on Cape Cod - the Amphibious Training Command under Brigadier General Keating was busily engaged in training Rangers in commando tactics. During the last few days of September, 1942, brigade boatmen worked with the Rangers and another new arrival, the 36th Infantry Division. This work culminated in the only large-scale maneuver the brigade ever held in the United States. They still refer to it as the “ Martha’s Vineyard Maneuvers” and participants are proud to relate their experiences in that maneuver to any listener. It was as realistic as actual combat except for the spilling of blood.

Extensive plans for the maneuver were made - the boats were put in tip-top shape, the men were carefully instructed in the duties they would perform, maps were checked and courses plotted, liaison contacts were made with the 36th Division and the Rangers. Arrangements were made to care for the large group of high ranking Army and Navy Officers who were coming from Washington and elsewhere to witness the maneuvers. Nothing was overlooked.

It was planned that on D-Day at H-Hour the main attacking force would land on Red Beach while supporting units landed on nearby Yellow and Green Beaches. Loading on the mainland was not started until dark fell. Troops and equipment of all kinds had to be loaded and the fifty-mile trip made through choppy seas and murky darkness to hit the far shore exactly at “first light”.

As the appointed hour approached, the guests and observers waited on a high promontory above Red Beach. Lieutenant General McNair, Commanding General of the Army Ground Forces, Brigadier General Sturdevant, Assistant Chief of Engineers, and Brigadier General Moses from Headquarters, Army Service Forces, were honored guests. Brigadier General Noce and Colonel Trudeau of the Engineer Amphibian Command, Brigadier General Keating and Colonel Wolfe of the Amphibious Training Command and Brigadier General Ogden of the 3rd Brigade were present as observers. 1st Lieutenant (later Lt. Col.) Karl W. Blanchard of Joplin, Missouri, was on the shore with these officers to invite attention to and explain evey minute detail. There was an intense air of expectancy, when, out of the inky blackness of the sea below, one lone boat approached. It came closer to shore and a boatman hollered, “Hey, is this Red Beach ?”

A snicker went through the crowd. “The Army Amphibs are lost”, someone remarked. But it was soon explained this boat was not in the landing force. It was an “enemy” boat sent out to set off charges to simulate firing on the landing force. Actually the landing craft were on the way in column formation dosed up in order to keep contact in the darkness and following the navigation boats in which were General Heavey, Lieutenant Colonel Ernest D. Brockett and Lieutenant Commander William R. Tucker, and others.

The seconds ticked away and H-Hour rapidly approached. From shore there was still no sign of the first wave of boats. Suddenly though, dim shapes loomed through the murk. The offshore wind had drowned out the roar of the engines. The boats were coming! In perfect formation the first wave ploughed through the surf toward the beach. They landed at exactly H-Hour. One officer later remarked that they may have arrived fifteen seconds too soon but that it was so damn cold that his watch had probably frozen for a few seconds. Our first real test had come out perfectly. It was a harbinger of success.

After the first wave landed, unloaded and retracted, the successive waves came in on schedule. Troops of the 36th Division and a battalion of Rangers clambered out of the boats and up the beach, simulating an attack on supposed enemy objectives. Planes overhead dropped a company of paratroopers to support the ground forces. Reports soon arrived by radio that the smaller landings on Yellow and Green Beaches, several miles away had clicked perfectly. Observers willingly admitted that troops poured ashore so fast the defenders would have been overwhelmed.

Shore Engineers marked the beaches and set about establishing the beachhead by building supply, water, gas and oil, ration and communication installations. The infantry was resupplied by the continuous waves of LCVs, LCMs, and nine LCTs manned by the Navy.

Hundreds of tons of actual supplies and ammunition were unloaded by the Shore Engineers and placed in marked dumps. All three beaches were linked at once by radio and later by telephone.

One incident during this operation earned for the brigade its first War Department decoration. 1st Lieutenant Ernest B. Huetter, 592d EBSR, of San Francisco, California, was in command of a wave of boats as they made their way across Vineyard Sound. Suddenly one of the boats burst into dense smoke and flames! The heat was so intense that all hands immediately abandoned the boat, and it was left running crazily about at high speed menacing the safety of other craft nearby. To further complicate the situation more smoke pots in the boat caught fire enveloping the area in great clouds of opaque smoke. Lieutenant Huetter first directed the rescue of all men in the water, then boarding the burning boat he brought it under control and subdued the flames with sea water. For his courage and quick thinking in the prevention of what might have been a tragic incident and the holding of the boat damage to a minimum, Lieutenant Huetter was awarded the Soldier’s Medal. This sort of courage and aggressive action is exemplary of the many acts of heroism that later became almost commonplace when the brigade moved into action against the Japs.

After two days the operation was called to a halt and pronounced a success. General McNair returned to Washington with the firm conviction that the Army had found the one link that was needed to carry the attack to the enemy -- the fast, accurate, and hard-hitting Amphibian Engineers.

War Birds Over Ord

The art of self-defense in one of its most advanced forms is being taught troops of an Engineer unit stationed at Fort Ord, and these pictures caught by Panaorama photogs will give you an idea of what it’s like to be under a strafing by bombers and pursuit planes.

Theoretically, a lot of boys were blasted out of their pants in fighting off these attacks, and still speaking theoretically, several of the planes shown here failed to return to their bases. That the planes had the edge in this training is an accepted fact, but when the real thing comes along these men will not be caught napping.

One touch of realism was provided both attackers and defenders, however, by the use of flour bombs. The accuracy of the Army airmen was amazing in many instances. For example, one stick of live such “bombs” was laid neatly into the open door of a sound truck stationed at the communications stand, and on another occasion a bomber laid a neat pattern on five machine guns spaced some 15 feet apart, providing guffaws at the expense of the surprised flour-bespattered gunners. One touch of realism was provided both attackers and defenders, however, by the use of flour bombs. The accuracy of the Army airmen was amazing in many instances. For example, one stick of live such “bombs” was laid neatly into the open door of a sound truck stationed at the communications stand, and on another occasion a bomber laid a neat pattern on five machine guns spaced some 15 feet apart, providing guffaws at the expense of the surprised flour-bespattered gunners.

Streaking across the parade ground at altitudes as low as 25 feet and from several different directions the planes proved difficult targets, but withal excellent training for the men on the ground. The picture directly below is typical of pursuit strafing tactics. Note low altitude of the plane in background.

In the panel at lower right, Capt. Elmer P. Volgenau, anti-aircraft officer, gets speed and altitude from pilots and transmits this information to the defending ground forces, The General and the Captain are in a bad spot here if the pilots decide to release a few flour bombs.

|