Chapter IX

The Leyte Landing

AT dusk on October 13, the huge amphibious fleet pushed out of Hollandia Harbor. The Amphibs were distributed on every type of ship from LSDs and APAs to LSTS. All were glad to see the mountainous shores of New Guinea fade into the distance. We had long awaited this invasion of the Philippines. Another smaller fleet carrying our 592d Task Group with the 1st Cavalry Division had just left Manus Harbor in the Admiralties. Still another fleet carrying the XXIV Corps was leaving from the Central Pacific Area. A total of more than six hundred vessels of LCI type or larger was to rendezvous between Palau and the Philippines and make a surprise landing, not on Mindanao where the Japs expected us, but on the little known island of Leyte. Company A, 542d, with fifty craft was to move up from Hollandia on the second echelon. The rest of the 542d Task Group at Biak was to follow as soon as transportation was available.

The next day while at sea the general details of the operation were released to the troops in a brigade memo from which the following is extracted

"1. You are now a part of a large force which is to make the initial landing on the Philippine Islands at Leyte. The purpose of this landing and the campaign to follow is to liberate the Filippinos from the Japanese. Unlike our previous campaigns, we will encounter here a civilized civilian population. Likewise, we will also be aided by native guerrilla fighters. Every effort, as far as compatible with the tactical situation, will be made to safeguard the lives and property of the Filippino People.

2.Heavy resistance from ground forces is not anticipated. However, after you land, be prepared for infiltration and night bombing raids, probably severe. In case of infiltration at night, knives, bayonets and grenades will be relied upon for protection. Firing of weapons will be kept to an absolute minimum. DO NOT FIRE UNLESS YOU KNOW YOU ARE FIRING AT AN ENEMY. Promiscuous firing will result in the killing of our own personnel. Movement after dark is prohibited until further orders."

Despite the size of the convoy and the fact that it was invading waters the Japs considered their own, there was no opposition to the convoy - no surface craft, no planes, no submarines. When three days from Leyte we heard that a typhoon had hit the small advance force which was to seize two islands at the entrance to the Gulf of Leyte, but had not prevented them from carrying out their mission. Seas had calmed by the time we entered the Gulf early on the morning of October 20, 1944.

White Beach, Leyte, Philippine Island. 22 October 1944.

While one LST unloads, another waits for 592 EBSR

“Cat” to complete jetty for unloading.

Just before the naval bombardment started that morning, a fast jap reconnaissance plane of a new type flew low over the entire convoy and, although every gun opened up on it, it escaped with the news of our arrival. The news it brought back to the Jap Headquarters must have astounded them. The Gulf was full of American ships from mighty battleships with 16-inch-guns to the small LCIs, hundreds of transports and large landing craft,, many of which were already disgorging the smaller LCVPs and LCMs for the initial assault on the beaches. Of the small landing craft which hit Red and White Beaches, about a half were operated by 2 ESB. All these craft remained on the Far Shore. The other half were Navy or Coast Guard and reloaded on the naval ships before they returned to be near shore. No Buffaloes were in these waves for finally we had gotten out of the coral-infested waters of eastern Australia and New Guinea to clearer waters and sandy beaches. A faster run from the transport area to the beaches was possible in landing boats than in the slow Buffaloes. Speed, of course, was important as the waves of boats approached the shore.

American troops unload supplies from LSTs in Leyte Gulf; Leyte Island,

Philippine Islands. 22 Oct 1944.

On the northernmost beach, White Beach, there was almost no opposition, only stray machine gun and sniper fire. On the next beach, Red Beach, opposition was stiffer. Not only did considerable mortar and machine gun fire sweep the approaches but some 75mm guns on the left flank opened up on us from hidden positions. Fortunately, these guns were in fixed emplacements and sited so that they could sweep only a narrow zone to sea and could not fire on the beaches proper. The three LSTs carrying Brigade Headquarters personnel were on the flank nearest to these guns. All experienced six or more direct hits. Casualties were fairly heavy on these LSTs. Major Michael B. Kubis of Maspeth, New York, Brigade S-2. was severely wounded; many other headquarters personnel sustained light wounds. Only by heroic and prompt action did the Navy fire crews succeed in quelling the fires on two of them. Four of our LCMs were hit by mortar fire, but none were lost. One rocket LCM, commanded by Lt (later Capt) Stevenson, of the Support Battery, was hulled by a 75mm shell, and was taken in tow by our salvage LCM and barely made the haven of an LSD where it sank inside the ship on the well deck. It was repaired on the LSD as it returned to Hollandia for a second trip and went back into action after it returned. A few of the Navy's LCVPs were sunk by enemy fire.

As anticipated from study of maps and aerial photographs, White Beach proved to be the most suitable beach. At Red Beach only one LST was able to approach close enough to the beach to unload. A second LST lowered its ramp and a bulldozer attempted to get to shore but slid into eight feet of water and jammed the ramp so it could not be lifted. All the other LSTs grounded by the stern with the bow in such deep water and so far out from shore that landing was impossible. Although this contingency had been expected and we had urged that pontoon causeways be brought in with the LSTs to land on Red Beach, none was available until they could be towed from the Dulag area, arriving late on A-night. No underwater obstacles or mines were encountered on the beaches. However, on the 2 LST landings on Cataisan Point, on A+2, three vehicles were damaged by booby-trapped bombs. The fact that we had surprised the Japs was proved by the large number of naval mines stacked on shore which had never been placed in the water.

White Beach, Leyte, Philippine Islands.

21 Oct 1944. Unloading gas from

592 EBSR LCMs.

Yellow Beach, Leyte, Philipine Islands. 22 Oct 1944.

Aerial view of LSTs on beach on A + 2.

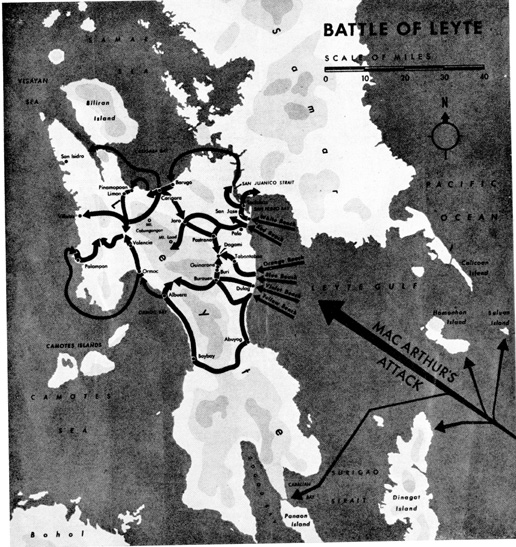

Muddy roads, steaming jungles, and steep mountains formed the battlefield of

Leyte, but it was on the roads that most of the action was fought; when there

were no roads, the troops often took to the sea in barges. MacArthur aimed

speedily to crush the enemy in twwo quick pincers movements, the first a smaller

closing in around beachhead area, the second a full - scale bear hug on the whole

island. To carry out the first step, troops moved from Violet Beach to Burauen

and from Red Beach to Pastrana, and - supported by other forces-closed in on

Dagami. The second step started off in the South with an advance to Abuyog

and Baybay, thence to Albuera; in the North quick progress was made by road

and sea to Pinamopoan. After a period of stalemate, US forces in rapid land and

sea movement closed in from all directions to join forces and destroy the enemy.

In addition to the difficulties encountered on Red Beach due to only one LST being unloaded by ramp, unloading on both Red and White Beaches was hampered by a very difficult swamp parallel to the beach and only 100 to 300 yards back from the high-water line. Numerous anti-tank ditches had also been constructed by the japs, but these were soon filled in by our dozers. In spite of difficulties, all the LSTs on White Beach and the one LST which was able to reach Red Beach were unloaded and able to retract by early morning Al. The eleven LSTs which were unable to beach on Red Beach were unloaded in the stream by LSMs and LCMs until three ponton causeways could be brought from Dulag and installed on Red Beach. On the morning of A+l unloading on these pontoon causeways was initiated. They proved satisfactory except for the difficulty experienced by LST commanders in grounding their LSTs near the causeways. Considerable time was lost in fitting the causeways to the points at which the LSTs grounded. On the night of A+ 1, one pontoon causeway was put out of action for several hours due to being hit by an LST coming in at almost full speed. While two or three sections of causeways were sufficient for the initial landing of each LST, it was necessary later to use as many as five sections per LST to reach the large grounded craft. This change was believed due only in part to a lower tide, the other reason being that the LSTs' propellers apparently built up a sand bar which wasn't there when the first LSTs came in for their landings. By 1800 on Al, six of the Red Beach LSTs had been unloaded and all the White Beach LSTs as well as several AKAs in the stream. The next day the remaining eight LSTS, two AKAs and one AK completed unloading and were able to leave by 17:00 completely unloaded and ahead of schedule.

Although shore work was interrupted by numerous air raids and air alerts, Navy craft were able to return to the Near Shore on the schedule set, and in the case of one echelon, a day ahead of schedule. Naval Beach Parties furnished by CTF 78 operated in conjunction with each shore party. The Naval Transport Groups furnished Transport Beach Parties to assist the Shore Party in unloading boats from the respective transports. These Transport Beach Parties were a great help to the Shore Party and operated most efficiently and with great energy. The result was that LCMs and LCVPs used in unloading these transports were able to return to the APAs for subsequent unloading so promptly that the average unloading time for the APAs was held to four and a half hours. As the APAs carried an average of 1300 troops and 450 tons of bulk stores and equipment, this meant that the average tonnage handled per hour was about 100 tons, which, it is believed, is a record for the Pacific areas. The fact that this Brigade had been associated with the Seventh Amphibious Force in numerous preceding operations, and knew its methods and many of its beach personnel, had much to do with the successful results. Almost a hundred thousand tons of supplies poured across the two beaches in the first six days. Only two of our shore battalions were involved in this work.

On the same day as the landings on White and Red Beaches, a third task group from 532d EBSR under Major Cecil J. Newton of Geneva, New York, supported the 21st Infantry Regimental Combat Team in a landing on Green Beach on Leyte, sixty miles to the south. The Japs had fled prior to our landing, so no opposition was received. During the next twenty days, our boats there carried seventy-two different patrols landing on forty-eight separate beaches in tropical, reef-infested south Leyte. (None of these 72 landings have been included in the list of combat landings made by the brigade as no fire was encountered. To the boatmen and patrols making the landings every one was a potential battle). Contracts were made with guerrillas and supplies delivered to them. Any japs who did succeed in escaping headed north for Ormoc.

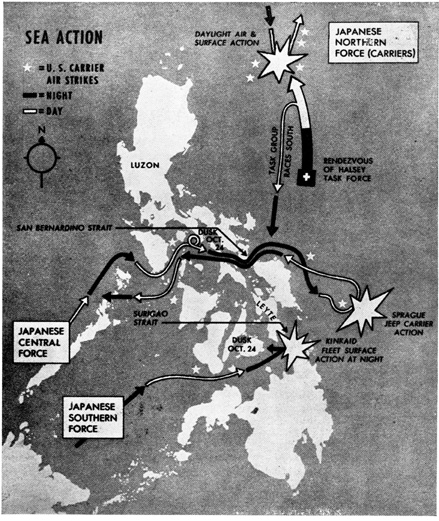

Most of the Amphibs on shore at Leyte did not realize at the time what a critical situation was happening on October 24. Few knew that the Jap fleet in three separate task forces was attempting to invade Leyte Gulf and. sink the many American transports there. At six o'clock in the evening of October 23, 1st Lt (later Capt) Mortimer A. Clift, Brigade S-2, of Great Neck, New York, had brought word to General Heavey that the Jap fleet was approaching. No other officers or men in the Tacloban area knew of the ensuing naval battle until the next morning, but some members of the Brigade knew from personal observation. It so happened that two of Major Newton's LCMs from Green Beach were in Surigao Straits south of Leyte at dusk when they observed a fleet pass eastward heading for the Pacific. They were thrilled, thinking it was an American fleet returning from the China Sea after covering our invasion. Little did they realize it was a Japanese fleet. For some reason the Jap ships did riot fire on the LCMS. Early the next morning both our shore and boat engineers near Green Beach heard cannonading to sea. Some saw a tremendous flash and knew a ship had exploded, but not until a day later was it learned that it was a big Jap cruiser.

The Amphibs near Tacloban heard by grapevine the next morning that the Jap fleet which came through the straits south of Leyte had been turned back by Admiral Kinkaid's Seventh Fleet. but that another fleet of Jap battleships was attacking our carriers off Samar. Soon as many as 50 naval planes from the carrier force were circling the incomplete Tacloban strip, radioing they were about out of gas and must land. Hurriedly clearing the incomplete strips, the exhausted naval pilots did wonders landing their planes. Some planes crashed, but luckily every pilot was saved. It was realized by all that these forced landings meant American carriers had gone to the bottom in the naval battles. What had the Japs lost?

Although it was days before details of the American naval victory reached the ears of the Amphibs, it was generally known with twenty-four hours that all the Jap naval forces, had retreated and that many of their battleships and cruisers had gone to the bottom. The brigade had been part of the American "bait" which led the Jap Navy out where the American fleet could hand it a disastrous defeat. The timing of the Jap attack was good. The Army had one foot on shore and one foot still in the water. Leyte Gulf was full of ships. Our land-based planes in Morotai could not reach the japs. But they had underestimated the fighting power of our Navy and, especially, of our naval carrier planes.

Victory at sea: A huge three pronged Japanese naval assault was

blasted apart on 25 October. The Japanese Central and Southern

forces came to us. Halsey’s fleet rushed after the Northern Force-

Fortune credit reads “Courtesy of Life, finish by Elmer Smith”.

The 1st Cavalry Division, old friends of New Guinea and the Admiralties, was anxious to force San Juanico Strait, the narrow and tortuous passage between Leyte and Samar. A fleet of eleven LCMs from Company A, 592d EBSR, under 1st Lt Albert F. Cappelli of Cranston, Rhode Island, was attached to the Cavalry for this mission. Two flak LCM gun boats under 1st Lt John H. Kavanagh of Rye, New York, were added from the Brigade Support Battery to convoy the Company A LCMS.

On October 23 the amphibious force pushed up the picturesque straits and made a landing without enemy opposition at LaPaz on Samar half way up the strait to invade Samar. The next morning an advance detachment of three LCMs carrying 200 cavalry under Staff Sergeant Richard D. McCoy of Van Wert, Ohio, convoyed by one of the flak LCMs pushed farther up the strait. One of the passengers was Robert Shaplen, the well known Newsweek War Correspondent.

Several miles through the narrow strait were accomplished without incident. Then Suddenly eight or ten Jap bombers came speeding down the strait. Spying the "defenseless" craft, the leading plane led off for a strafing and bombing attack on the head of the convoy. Little did he realize that these LCMs would open up with twentv 50-caliber machine guns not to mention the 20mm and automatic 37mm guns on the flak LCM. The first Jap plane dived in to the hail of gunfire and immediately exploded into flame. A second one following met the same fate. The others veered off from the terrific fire put up by our boats. Navy Hellcats arrived and attacked the others. It was a hot time for a few minutes.

On October 20, 1944 two years, seven months;, nine days after he left Corregidor in a PT boat,

General MacArthur wades ashore with his army in the Philippines.

Leyte, Philippine Islands, April 1945.

New Flak LCM No. 759 built by 562 Engr. Boat Maint.

Bn. and 162 Ord. Maint. Co. Left to right Pvt. George

N. Messick, Tec 5 William Adams, Tex. 4 Raymond

Durstine;, Tec. 5 Alvis Knight, Tec. 5 Jack Rowe.

Lower Right: Capt. James R Virtue.

Robert Shaplen described the rest of the trip in Newsweek as follows:

"One mortally wounded bomber came down directly toward us. At the last minute the pilot gave her a twist. The plane spun into the ocean 150 yards away. Before he hit the water the Japanese pilot dropped a bomb at one of our gunboats. It missed by a few feet. As the bomber wreckage sank, the pilot came up to the surface, revolver in hand and was shot by our gunners. His head was blown off. Guided by a Filipino, the Americans landed and dug in. The next morning Jap Zeros made two diving runs at the gunboats. A bomb dropped just off the stern of one. Shrapnel killed eight men and wounded seventeen. But the Americans shoved on to seize two north-coast towns on deep protected Carigara Bay, one of the main allied goals."

Later, on 24 October, Major Smith of the Cavalry loaded a thousand men on eleven LCMs and three LCIs for the the final push up the Straits. While he and Lt. Cappelli were making last minute preparations, a lone jap light bomber suddenly appeared over the hills to the west and dived for the convoy. All eleven LCMs opened fire on the suicidal jap and should share the credit for the plane's immediate destruction with the three LCMs. One of the LCM coxswains, T/4, Joseph Kaplan of Richmond Hill, New York, was hit by shrapnel and hospitalized. After this interruption the Convoy made the trip up the Straits without any trouble and made an unopposed landing at Babatngon that afternoon. The LCMs anchored off the beach and spent a peaceful night-serenaded by happy Filipinos who paddled around the fleet in bancas singing, "God Bless America" to their "Liberators."

An LCVP which participated in assault landings from Lae, New Guinea to Leyte, Philippine Islands - a distance of 2,000 miles. An LCVP which participated in assault landings from Lae, New Guinea to Leyte, Philippine Islands - a distance of 2,000 miles.

The next morning was not so peaceful. Four Jap medium bombers swooped down from behind Babatngon Hill and suddenly attacked the fleet. They came over in pairs, one dived for LCI 23 that was lying in close to shore while the other went for LCI 238 that was well out in the stream. The LCMs that were under way quickly dispersed and opened fire, the ones that were anchored lost no time cutting their lines and manning their guns. LCI 23 received a bomb hit near the water line off her starboard quarter - a large hole was knocked in her side and many of her crew were wounded and killed. Lt Cappelli aboard LCM 500 immediately started over to render aid to the stricken vessel. As he approached the LCI he noticed a sailor drifting along in the currnt in his life belt, face down, obviously unconscious, and dived into the water to get him. As LCM coxswain T/4 Reuben G. Personen of Elkin, Michigan, maneuvered his boat to get the man aboard - one of the planes made a strafing run, over the area while another dropped a bomb near the other LCI. By that time Lt Cappelli, who was fighting the current with his heavy burden had discovered that the sailor he was trying to save, unfortunately, was dead. The heavy anti-aircraft fire from the LCMs must have discouraged the Jap planes for they made only the single attack and winged for home - one of them trailing black smoke.

The LCM was put alongside the LCI to take off the wounded. After the wounded were hurried ashore to the Cavalry aid station, three LCMs towed the disabled Navy LCI onto the beach and helped to camouflage her with trees and foliage. Lt Cappelli with five LCMs loaded with eight dead and twenty-five wounded sped back to Tacloban, only to be delayed right at the dock by a heavy air raid.

The next morning six LCMs lying off Babatngon Beach were attacked by a lone Jap bomber, who came in low for what he thought would be an easy kill. He was an easy target and the gunners just poured it into him. The surprised pilot turned and fled with one engine out and trailing black smoke behind. A crashed plane, identical to this one, was found shortly afterwards by a Cavalry patrol a few miles inland, and there is every reason to believe it was the same plane.

From then on new landings were made almost daily on Leyte and Samar Islands, and the towns of Barugo, Santa Cruz, Carigara, Villa Reale, Caliliga, and many smaller barrios became Cavalry outposts and links in the ever-growing supply chain. The venturesome Amphibians volunteered to “recon" the small islands in Carigara Bay and were the first to land onBuad, Lamingao, Daram, and Quintarcan Islands, often playing hide and seek with jap patrols.

Macajalar Bay Mindanao, Philippine Islands, 10 May 1945. Filipinos help unload Co. B, 542 EBSR LCMs Macajalar Bay Mindanao, Philippine Islands, 10 May 1945. Filipinos help unload Co. B, 542 EBSR LCMs

On the night of 30 October a new enemy appeared - a tropical typhoon, complete with mile-a-minute winds and gigantic waves. It caught part of the LCM fleet in Carigara Bay and did its best to sink every boat in it. Luckily, only one boat got into serious trouble. It's coxswain T./4 William L. Cecil, of Dublin, Virginia, put up a game fight but was compelled to abandon his LCM. He was rescued from his sinking craft during the height of the storm by T/4 Joseph R. Crummie of New Kensington, Pennsylvania, and his boat crew.

During November the heavy rains practically obliterated the roads in Northern Leyte and Samar, making the Cavalry outposts completely dependent on the LCMs for all resupply, replacement and evacuation. From daylight to nightfall the Amphibians sped up and down the Straits, west into Carigara Bay, east into Villareal Bay, hauling ammunition, troops, supplies and evacuating casualties. A Navy order prohibited running the Straits at night for fear Jap craft might come in undetected. However, the night of 20 November fifty-three casualties awaited transportation at Babatnogon to the hospital at Tacloban, so Lt Cappelli broke the rule and made the first trip. From then on casualties were run in to Tacloban regardless of time or weather.

Macajalar Bay Mindanao, Philippine Islands, 10 May 1945. Lt Gen. Robert L. Eichelberger stepping ashore from Co. B, 542 EBSR LCVLP. Macajalar Bay Mindanao, Philippine Islands, 10 May 1945. Lt Gen. Robert L. Eichelberger stepping ashore from Co. B, 542 EBSR LCVLP.

These "A" Company, 592d LCMs stayed with the 1st Cavalry Division, participating in all their operations until they were relieved to stage for the Luzon show. Company A, 542d, then took over the job and continued to supply and evacuate for the Cavalry Division. Meanwhile, our boat and shore engineers had been working day and night unloading LSTs on White and Red beaches and Liberties out in the stream. First priority went to getting steel matting onto the Tacloban airstrip. This was no easy job for by a strange slip-up the heavy landing mat had been loaded deep in the holds of the freighters, instead of near the hold where it could be quickly unloaded. It was necessary to first unload the cargo and many trucks before the pierced plank for the airfield could be reached. Nevertheless, by working night and day until men were ready to drop in their tracks and disregarding the Jap bombings, the flow of steel mats reached the strip just before the aviation engineers had the field graded and ready to commence laying the metal runway. The Amphibs saw to it that the aviation engineers never had to wait for the mat coming off the Liberties anchored miles out in the Gulf. One night seventy-one separate Jap attacks were made on the engineers laying the strip and bringing in matting from the ships. Exactly a week after D-day the field was ready. The first land-based fighter which had flown 2000 miles from New Guinea came down on the just completed strip. Amphib engineers joined the aviation engineers in wild cheering as the welcome P-38's gracefully landed. General MacArthur was there and personally greeted the commander of the P-38's. He was as glad to see them as the rest of us. Within an hour the planes refueled and were out against the Japs, relieving the exhausted carried planes.

During all these operations we were undergoing the, miseries of a wet season, and of course, 1944 would be a much wetter year than usual at Leyte. One 80-knot typhoon hit us early in November and another one later in the month. The boatmen had to keep their craft headed into the wind with anchors down and engines full speed ahead to keep from being driven ashore. A number of the larger naval craft, with larger surfaces exposed to the terrific wind, were unable to hold and were beached. One PT boat was washed inland so far it had to be abandoned.

The light Leyte roads were soon churned to a morass by the heavy Army trucks and twenty inches of rain a week. Almost everything had to be moved by boat. Troops, ammunition and supplies were carried on the forward trips with sick and wounded on the return trips. Only one landing strip could be kept in operation due to the heavy rains. Work was rushed on new strips and our lighterage gave priority to unloading steel matting for those urgently needed airfields. There were always more demands for our craft and for the LCTs furnished by the Navy than could be met. There was a daily battle to determine who would get priority on available craft. In the Leyte-Samar operations we found the exact situation for which the brigade had been formed. Its facilities were utilized to the maximum. Our shore engineers with attached port, DUKW truck, and service companies and Filipino civilian labor, were extremely busy unloading ships over Red and White beaches. Every available means of lighterage was used, from the Navy LSTs and decked barges propelled by outboard motor unit, known as Sea Mules, to our small LCMs, LCVPs and DUKWs. We established "sub" beaches to reach outlying detachments and our boats were kept busy in movement of troops and in resupply echelons throughout the islands. Radar units were moved up to isolated areas. Guerrillas were picked up and moved from point to point.

The "Luck of 2 ESB" was well illustrated during the heavy Jap bombing of our shipping in Levte Gulf. The bulk of Brigade Headquarters and Brigade Service Troops was aboard the Liberty Ship Samuel K. Barlow. A Jap dive bomber dropped a 250-pound bomb squarely on the bridge, but it failed to explode to the vast relief of everyone. The plane was brought down by gunners on the Barlow and crashed into the sea close beside the transport.”

Our Hydro Survey party, commanded by Lt Col William R. Tucker of Camp Hill, Alabama, who was detailed to the brigade in 1942 from the Coast and Geodetic Survey, rendered valuable service in finding suitable beaches for Naval landing craft on both Leyte and Samar, and in locating and buoying a channel to the dock in Tacloban. He worked close behind the advancing infantry. It was feared the channel would be too shallow to allow fully loaded Liberty ships to proceed to the dock, but a suitable channel was found. Strange to relate, it was free of mines. The japs had several hundred horn pronged naval mines ashore, but none had been installed. Colonel Tucker also found the dock in perfect shape, except for one small Jap ship sunk at one end of the dock. This ship had been sunk by American air attack. No booby traps were found on the dock. The 1st. Cavalry Division having secured the land areas around the dock, Colonel Tucker guided the first two Liberty ships to the dock on the afternoon of the fifth day, and over a thousand tons of cargo were unloaded the next day, gradually increasing to 3000 tons a day as unloading facilities and warehouses were obtained. By this time the Japs awakened to the value of the dock and bombed it heavily, inflicting casualties and damage to both ships and dock but not stopping the work. The shipping and landing beaches received their share of bombing, too. Outside of the crude coral jetties at Biak. this Tacloban dock was the first dock we had found intact in any of our operations in the Southwest Pacific. It made us think we were getting back to civilization. It is not intended to burden this history with logistics, but members of the brigade might well be interested in the following extract from a report submitted by Gen Heavey to GHQ on work of the brigade in Leyte:

"For your information 2 ESB has handled the following monthly cargo (DWT) over Red and White beaches from 20 October 1944 to 15 March 1945, the day it was relieved from this work

Red Beach White Beach

20-31 October 29,071 63,125

1-30 November 23,548 75,309

1-31 December 43,177 54,074

1-31 January 38,072 54,074

1-28 February 23,929 40,134

1-15 March 10,226 17,870

In addition 2 ESB operated or supervised Catmon Hill, Tanauan, and TolosaBeaches. Total tonnage handled across these beaches for the period 20 October-15 March amounted to 97,51.9 tons."

The capabilities and efficiency of the brigade is well summarized in Rear Admiral D. E. Barbey's report of the Leyte Operation:

"Shore Parties in this operation were, provided by the 2d Engineer Special Brigade. The splendid work of this organization contributed materially to the rapid unloading of ships and dispersal of supplies under most difficult conditions. The 7th Amphibious Force and the 2d Engineer Special Brigade have been associated in numerous amphibious operations in the past; complete understanding has been achieved through this close association and was reflected in the smoothness with which the LEYTE unloading operations progressed."

ORMOC LANDING

During November the Japs were slowly driven by our infantry from eastern Leyte over the mountains into rugged western Leyte. The Cavalry Division had been moved by 592d LCMs to Carigara Bay on the north of Leyte and was pressing south. However, Jap reinforcements and supplies kept pouring into western Leyte from Luzon, mainly under cover of darkness. The Sixth Army decided to make an amphibious landing south of Ormoc to attack the Japs in their rear and to cut off their supply and reinforcements.

A boat detachment of Company C, 592d, under lst Lt Samuel D. Harper of Florence, South Carolina, supported by our rocket LCM and one flak LCM of the Support Battery under 1st Lt (later Capt) Edwin T. Stevenson made an amphibious landing south of Ormoc with-the 7th Division on December 7. The Support Battery craft concentrated on Ipil with both barrage rockets and 75mm gun fire. Rocket fire on Ormoc from Lt. Stevenson's rocket LCM set the town on fire and destroyed large amounts of enemy stores. The landing was successful with only a few casualties, but that afternoon all craft were subjected to a heavy Jap air attack. None of our boats were hit but the larger Navy craft were not so lucky. Two LSMs and two APDs went down in the furious attack. Our small landing craft rescued many sailors who had to abandon ship. The next day six LCMs loaded with casualties left Ormoc for Bavbay. They were under continuous air attack all the way by Japs who were thoroughly aroused by our Ormoc invasion. Lt Harper and three of his boatmen were seriously wounded. 1st Lt Charles E. Stephens of Gilmer, Texas, took command and skillfully maneuvered the boats to bring them all safely to Baybay although several others were wounded during the day. No boats suffered direct hits, but all received fragments. It was one of the hardest days our boatmen ever experienced but the gunners were not taking these attacks lying down. Two Jap planes were definitely shot down and others were undoubtedly damaged. Lt Harper, Lt Stephens and eleven men won the Bronze Star Medal for their heroic action. Lt Edwin T. Stevenson of the Support Battery was awarded the Silver Star Medal.

Back on Red Beach on eastern Leyte on the early morning of December 10 there was a terrific explosion when 80 tons of explosives let go for some unknown reason. Much valuable equipment was destroyed but fortunately the brigade suffered no casualties, although, many had close calls. Other units suffered casualties.

FIRST LANDING ON MINDANAO

In the meantime two LCMs from Company C, 592d, made a surprise amphibious landing on Mindanao, as much of a surprise to them as it was to the Japs. The two craft loaded with bulldozers were sent under Staff Sergeant Henry W. Telker of Warren, Ohio, to nearby Samar Landing. Out in Leyte Gulf they got blanked out in tropical fog and storm and followed a faulty compass course. After an all-night trip through rain and storm they were relieved at dawn to see an island ahead. Not sure where they were, one LCM cautiously landed as the other stood by. Guerrillas rushed out to greet them. Telker asked them: "What island?" "Mindanao," they replied. "Any Japs about?" "Oh! yes, four thousand of them over there on that ridge." Telker lost no time reloading and heading back for Leyte, but the japs on the ridge spotted him. His boats were only an hour out on the return trip when three Jap planes came from the direction of Mindanao strafing and bombing. Telker's four gunners put up the hottest fire they could and the Jap planes disappeared without inflicting any damage except a few holes on the boats about the water line. Two hours later the Japs hit again with three more planes. This time a l00-pound bomb hit one of the dozers in the boat. Luckily, it was a dud and bounced off harmlessly into the sea. The next day Radio Tokyo reported that an attempt to land on Mindanao had been repelled with heavy losses to the Americans. None of our men were hit and the damage to the boats was soon repaired.

PALOMPON

On Christmas Day the 592d participated in another landing. This force was under 1st Lt. Kenneth R. MacKaig of Glendale, California. Our Support Battery had recaptured 300 rounds of American 75mm ammunition at Ofmoc which the Japs had captured at Bataan in 1942 and brought to Ormoc to fire at us. Instead, our gunboat and rocket LCM had the pleasure of mixing these 75's with rockets to pour on the enemy at Palompon, north of Ormoc. This was our last combat landing on Leyte for now the Japs were encircled and sought the mountains. But our job was not finished. For many months we were to operate boats in and out of Ormoc, attacking outlying islands where Jap garrisons had to be mopped up and supplying the many separate radar and infantry detachments. In early December Companies A and F, 542d, had started moving troops and supplies from White Beach to the northern tip of Leyte. From there the troops pushed south on Ormoc to compress the Japs in conjunction with the simultaneous drive from south of Ormoc.

SAMAR

North of Leyte lies the large island of Samar. Shortly after the initial landing on Leyte, our 592d boats had pushed through the narrow strait between the islands and landed cavalry in Carigara Bay. Other forces were landed on Samar and soon overran southern Samar. Then followed a series of small amphibious landings as the Americans pushed up the western coast of Samar. These were participated in by boat units from all three of our regiments. On January 27, 1945, three LCMs of Company A, 542d, were loaded with 37mm guns and infantry mortars of the 381st Infantry and proceeded to St. Margherita village, sixty miles up the coast where a large concentration of japs was reported. The Japs were caught unprepared for this fire from the sea. Our Guerrillas later reported 180 Japs were killed and 60 wounded by this surprise attack.

On Catmon Hill Beach;, Leyte, Philippines, 1944. Gen. Heavey and staff officer. On Catmon Hill Beach;, Leyte, Philippines, 1944. Gen. Heavey and staff officer.

By this time the 532d, less Company A, had left Leyte for the Mindoro landing, which is described in the next chapter, and the 592d had loaded out for two landings on Luzon which are also described later. This left on Leyte Brigade Headquarters and Special Troops, the 562d Boat Maintenance Battalion less the maintenance companies with the 532d and 592d, and the Medical Battalion less its companies with the 532d and 592d task groups. The 542d Regiment and the 1570th Engineer Maintenance Companies had moved in echelons from Biak to Leyte. In early February, 1945, the last elements of the brigade finally closed out in New Guinea. The 542d was kept busy running Red and White Beaches at Leyte as well as supplying many outlying detachments and radar stations.

The 262d Medical Battalion did a wonderful job at Leyte. In the initial landings its units invariably had the first medical set-ups on the beaches. They handled the evacuation of all casualties to ships in the Gulf and also those evacuated by air. For its fine work the entire battalion was awarded the Meritorious Service Plaque.

On January 15, 1945, a 592d task group loaded out a 7th Division force at Ipil and landed them successfully on Ponson Island west of Leyte. In this operation fifty-six Buffaloes, many carry 75mm howitzers and flame throwers, were attached to the Amphib group of some twenty-five cargo LCMs and three LCMs from the Support Battery. This landing, was followed two days by a similar landing on nearby Poro Island. On the morning of January 19 a single enemy Zero tried to strafe the beach but was driven off by the heavy antiaircraft fire from our boats. That night several planes bombed the beachhead but with little effect

A detachment of Company C, 592d, under lst Lt James E. Klug of New York City, had been operating boats around southern and western Leyte and had a staging point at Liloan. When their duties were completed and they were ordered to return in preparation for Luzon landings, it was found that they had made a tremendous hit with that Filipino community. Letters of appreciation from the justice of Peace, the Women's Auxiliary, the Mayor and what not flooded brigade and higher headquarters. Evidently, our men were as good at making friends as they were at making war.

In the Leyte and Samar areas out craft during February and March worked with the 96th Division, the 38th Division, the Americal Division, the 1st Filipino Infantry, and Filipino Guerrillas in widely scattered operations. Company A, 542d, furnished many of these missions, later being relieved by Company C, 532d, under 1st Lieutenant (now Capt.) Henry Meiggs of Palo Alto, California.

On February 19 Company A, 542d, set out from Catbayog on western Samar for a series of landings with the Americal Division to mop up the important San Bernadino Straits between northern Samar and southern Luzon. These were the straits through which one element of the Jap fleet advanced for the battle of Leyte Gulf. After finding Datpuri Island suitable for landings this task group landed at Allen on the coast of Samar. From there they landed a reinforced infantry company on Caput island where they wiped out a small force of japs. Landings were then made on several other nearby islands, the most important of which turned out to be Biri Island. Guerrilla information led the Americal Division to believe the beach there not strongly held by japs. An air strike by six Corsairs was scheduled before the landing and several PT boats strafed the beach. But when during our landing, the wave of two LCMs loaded with infantrymen went in at eight o'clock for the landing they met furious fire. At 600 yards they drew .50 caliber machine gun fire but kept pushing on. When only 300 yards out, 20mm gun fire joined the machine gun fire from the beach. At 150 yards mortar shells began bursting around the boats. The infantry passengers were flat on their bellies in the bottom of the boats and thus avoided much of the fire but our crew had to keep their exposed positions. The LCM on the right flank hit a reef 25 yards from the shore and stuck hard and fast. The ramp could not be lowered as the ramp cable had been shot away. In the meantime the left flank LCM had gotten to within 50 yards of the shore but the engine man had been killed, the coxswain, wave leader, and two seamen all wounded. The LCM out of control turned broadside. The seaman on the ramp realized no one was at the wheel and, although already wounded, ran to the stern and took over the wheel. Seeing the other boat in trouble he skillfully maneuvered his craft to get a line to it and, upon orders of the infantry commander, both boats withdrew out of range. Of the eight members of 542 in the two crews, two were so badly wounded they died of their wounds and four others were wounded. Yet both craft with their many passengers, over thirty of whom had been hit, were brought back out of the murderous fire. One of the boats had almost a hundred holes in it, the other one over fifty.

Not to be deterred, a new plan for landing on the island was worked out. At one o'clock in the afternoon the boats went in again landing without difficulty on the rear side of the island. The infantry rapidly pushed overland to the beach where the original landing was attempted. This attack surprised the Japs and all sixty-eight of them were killed. It was found that the Japs had eight machine guns and two 20mm guns and a knee mortar on that first beach to oppose our initial attempt. It happened that some of the boatmen on this landing had also participated in the hot landing at Wakde the previous April. They all agreed the Biri Island fire was worse than at Wakde. For their heroism that day four of our men were awarded Silver Stars, and two Bronze Star Medals.

More than in any operation since the days of Lae and Finschhafen the brigade felt that in the Leyte operation it had earned its salt. Our craft were indispensable to the success of the operation. Our shore engineers, signal and medical personnel felt that every day they were doing vital work. Our gunners had real jobs to do shooting down many Jap planes and driving others off. The rocketeers of the Support Battery knew their rockets were killing many Japs. The 75mm installed so ingeniously in the bow of a flak LCM at Finschhafen paid huge dividends.

In one important respect, the Leyte operation was unique to members of the brigade, and in fact to all Southwest Pacific troops. We had all read of tumultuous welcomes given by liberated peoples to our men in Europe. This was the first time it happened to us. Bivouacked in New Guinea and the Bismarcks, perhaps the least developed corner of the World, we saw photos and newsreels of crowds cheering American Soldiers, crowds weeping tears of joy, young ladies embracing GI's on trucks, flowers scattered in French and Belgian village streets. But somehow those things didn't happen to us. The scenery for our war consisted of frowning forest-clad mountains, sago swamps eerie at night with innumerable queer sounds, a vast, excessively fertile wilderness where dinosaurs would scarcely have seemed out of place.

At Leyte, suddenly, it was different. It is true the Filipinos had little to offer of material value. The Japanese had reduced them to utter poverty. But they were glad to see us. They welcomed us warmly like friends who had been away for a long time. Very few of us had ever seen a Filipino before. It was a pleasure to find them a neat, sturdy little people. The children joyously greeted us with fingers extended and crying out "Veectorie." The girls were actually cute and the men, though small of stature, were well built and good looking and their skins were a warm brown. Their firm handshake and friendly man-to-man welcome-in English-made you feel good. They went to work on the beaches, they gave us invaluable information about the Japs and the Guerrillas soon showed themselves to be a strong ally. At Leyte we realized that we really were fighting a war of liberation.

AT THIS POINT pages 119 through 122 ARE MISSING!

encountered every form of enemy fire, land, sea and air. 26 December 1944 will always be a vivid recollection for 532d personnel.

Simultaneously with these activities in December the Regiment ran several small but important boat missions from San Jose to points North. These missions were mainly of a resupply character and important for observation and patrol purposes.

On U-Day a reconnaisance party of the 532d consisting of Sergeant John McConnell, Corporal George F. Burke of Leadville, Colorado; Corporal Harry Rustay of Phillipsburg, New Jersey; and Private Calvin Transue of South Coffeyville, Oklahoma, moved with an advance detachment of the 503d Paratroopers through kunai grass nine feet high along the tracks of San Jose. Aerial reconnaissance had revealed the tracks and a few cars, but no locomotives. Three hours after H hour this party reached the Roundhouse. They were all old railroad men, who in the heat and sweat of New Guinea had dreamed of the glory of riding the tracks once more. "Better a hundred stops a run for hot boxes than New Guinea and its trials," had been their refrain.

The former Filipino employees of the line met them at the yards and expressed eagerness to cooperate. From these Filipinos they learned that effective sabotage had prevented the Japanese from using the line. Ingeniously they had stripped the locomotives of vital parts and buried them in hidden places around the mill. They had cut down the coils in the telephones and rendered the communications system inoperative. Thus in three years of Japanese occupation scarcely a wheel had moved over the line.

The party learned that there were 43 miles of track; that of equipment there were two 50-ton engines, three 10-ton engines and one tractor engine. In the yard stood four hundred cane cars and six standard cars. The average age of this rolling stock was twenty years. The average daily hauls in the sugar season had been only one hundred tons.

The railway crews of our Shore Party immediately went to work. Ten hours later No. 7's bell clanged and the tractor engine was dispatched to a Signal Corps unit for stringing lines. This was the first time in MacArthur's drive from Port Moresby on the South side of New Guinea that railroad facilities had even been encountered. It took the Amphlb railroaders only ten hours to start making use of them.

The next call some hours later came from Caminawit. Roads were in very poor condition and there was urgent need for evacuation of wounded to the San Jose Hospital. Number 9 would have to be dispatched. This was an old German diesel in which the Japanese had attempted to use too heavy a fuel and had clogged the fuel system. The proper oil, however, was still lacking. Pablo Carillo, who had been master mechanic on the line, was consulted. He immediately busied himself with cleaning the fuel system. Other heads grappled with the fuel problem, but the outlook appeared rather hopeless. Suddenly there was an ear-splitting groaning and throbbing and No. 9 moved out of the Roundhouse. Carillo had solved the impossible--No. 9 was operating on coconut oil. Thus the "Coconut Oil Special" started on its first errand of mercy and successfully evacuated seventeen wounded of the Navy Party.

No. 4, a wood burner which had been converted for oil, was the next to go into operation. This old timer made the most memorable runs of the whole operation. Every night it carried wounded up to the San Jose Hospital. Its course was emblazoned across the blacked-out countryside. Being a wood burner it sent up a fifty foot geyser of sparks and rode through the night a pillar of fire, but nonetheless saving for the surgeon precious minutes in his battle for lives. When air alerts and raids came, there was no stopping and blacking out. It had to continue full speed ahead. No one, crew member, nurse or evacuee - will ever forget those mercy trips. Thereafter activity in the yards doubled. To avoid strafing by enemy planes, runs were usually made at night as was much of the repair work also. Track repair work was particularly difficult under blackout conditions. In a short period, four locomotives, the tractor engine and three hundred and sixty-five cars were in service.

It was a group of former railroad men among 532d personnel who contributed largely to this magnificent achievement. Their combined railroad experience totaled seventy-two years. In that group were Sergeant John McConnell, Corporal George F. Burke, Sergeant John Anderson of Shoshone, Idaho, Corporal Richard Hanson of Bloomington Indiana and Robert Boat of Denver, Colorado; Privates First Class Carl Dahl, of Sioux City, Iowa, Manuel Lujan of Merced, California, James Diem of Ford Spring, West Virginia and George Baker of Marcola, Oregon; and Privates Albert Peterson of Shelly, Minnesota, Stephen Napp of Bronx, New York, Virgil Chambers of Chipley, Florida, and Private Calvin Transue. To their efforts were added those of some forty other men who had not previously worked on any railroad.

Company Dunder the command of Captain Gerald E. Peterson of Blooming Prairie, Minnesota, was in charge of railroad operations as well as the operation of the machine shop, electric plant, ice plant and water supply of San Jose proper. These utilities serviced all headquarters and dumps situated within the town proper. They were put into operation speedily as had been the railroad. Here, too, the problems were akin. The replacement of worn parts taxed ingenuity. Outstanding in their work in the utilities field were Staff Sergeant Arthur Houghlan, Sergeant John Heddon, Corporal Harry Gates and Privates Panfilio Duenez and Frank Goenkel.

In the month of January, major attention and effort were devoted to port and unloading activities. Much air force equipment, supplies, and ammunition had to be handled. White Beach, which had been closed in late December, was again reopened. Many improvements were made on both Blue and White Beaches to facilitate the handling of heavier tonnage. Central control towers, from which Boat, Beach and Signal sections operated, were constructed on both beaches and the coordination of these activities was appreciably improved thereby.

There was a notable increase in traffic borne by the 532d Communications Section. Their blinker tower directed shipping to assigned anchorage and relayed unloading schedules. Radio telephone handled inter-beach messages. Semaphore posts guided small craft unequipped with radio or blinker. Their radio stations handled messages from shore to high echelons. The telephone exchange was integrated with the San Jose network. The Army and the Navy made the fullest use of this network of communication.

The Boat Battalion operated during the month four important tactical missions, which were chiefly resupply of outlying radar and infantry units. The first of these was to Marinduque Island, which is only twenty miles from the shores of Luzon. All the missions were carried through unfriendly waters, some through waters with treacherous coral reefs, but all craft returned safely. The total boat mileage covered by these missions was 3,752 miles. 532d boats were also employed in assisting five PT boats to refloat after they had run aground on reefs near Mangarin Bay.

On 9 January with the invasion of Lingayan Gulf, Luzon, enemy pressure on Mindoro was relieved. Subsequent to that date there were but few air attacks. For the first time since U-Day personnel were able to enjoy an uninterrupted night's rest. Up to this date the men had assumed posts nightly on the perimeter defenses. Camp installations were solely of a primary character. Practically no tents were erected. The men had been sleeping on cots in the open at their perimeter posts right next to their foxholes. There was little shade from the hot sun and little protection from rains if they came. Fortunately though, while operations at Leyte were in a sea of mud, Mindoro was in the middle of the dry season.

Immediately after the lifting of enemy pressure much effort was devoted to preparing camp sites and erecting installations. For the first time the men had the opportunity to appreciate the excellence of their location. Pleasant climate and dry weather was in marked contrast to the rain and primal ooze of Leyte. Open, level fields allowed the organization of an athletic program. Adequate ball fields were now available. In truth it can be said that the finest living conditions since arrival overseas were now enjoyed. After its long hard days from Nassau Bay to Leyte and on to Mindoro, it is certain that the men of the 532d deserved a rest and a break on the weather.

Throughout the entire period of the Mindoro operations the Regiment had never had present for operational purposes the full complement of its boat strength. One company had been attached for operational activity to a task force at Ormoc, Leyte and operated along the western shores of Leyte and Samar and to the outlving Camotes Islands and even as far as Masbate.

In March the Boat Battalion participated in two assault missions off Mindoro. The first of these was against Lubang Island. In mid-February a reconnaissance of the island had been made by a small 532d party under the command of Captain (later Major) Jack C. Fuson of St. Joseph, Missouri. At that time offshore soundings were made within sight of the enemy garrison but no fire was encountered. On March 2 when the actual landing was made, it was different. Such heavy offshore fire was received that the 532d LCMs under 1st Lt. Clyde Oakley of Sayville, Long Island, New York bid to wait two hours for the enemy to receive a second pasting before the LCMs went in for the landing.

On 12 Match, three assault landings were made by 532d boat crews under the command of ist Lt. David B. Bernard of New Haven, Connecticut, on Iliban, Simara Island, and Romblon Island. While at anchorage at Iliban our boats were fired upon by enemy machine gunners. No casualties were inflicted.

Daily throughout the month, resupply missions were run to various small islands and outposts on Mindoro and off the coast. And while no unusual incidents were connected with these missions, skilled seamanship and constant vigilance were always in order.

In April Boat Battalion detachments were operating from Mindoro, Romblon Island, Palawan, Leyte, Samar, and Masbate. Company "B" was ordered to Batangas in Southern Luzon for lighterage operations at that newly opened base.

Also in April a Shore Battalion party under direction of a Naval Salvage Officer completed the salvage operations in which they had been engaged since January. The Libertv Ships John C. Clayton and Juan De Fuca both of which had been badly damaged by jap suicide crash dives in the early days of the Mindoro operation, were made ready for sea. Patches had been welded over holes torn open by torpedoes, keel stiffeners had been installed and bulkheads shored and braced. Our volunteer crew in a new field of endeavor worked for days in bilge water but felt repaid for their effort when the Liberties went back into service. Another evidence of our versatility!

In March 1945 Lt. Colonel Robert J. Kasper, Executive Officer of the 2d Engineer Special Brigade, succeeded Colonel Neilson as Regimental commander. Colonel Neilson went to an engineer job in Luzon. After the April operations the 532d settled down to duties largely routine and made preparation for a period of intensive training and for the Palawan operation. The announcement of VE day in May warmed every heart and brought new hope for an early victory over Japan. Mindoro was to remain as the site of Regimental Headquarters of 532 for almost a year. The men of 532 thus spent more time in Mindoro that at any other station since the formation of the Regiment back in June, 1942.

|